Romania vs TikTok: democracy dying or democracy defending itself?

The facts

On 24 November, Romanians voted in the first round of the presidential elections.

Alongside the candidates of the establishment (social democrats and national liberals), accused not without all the wrongs of keeping a corrupt system alive, ran George Simion, leader of a Eurosceptic right-wing party, and two populists of the opposite sign: Elena Lasconi and Călin Georgescu.

The former, with its Union for the Salvation of Romanians, is inspired by European values to make the country more modern and transparent.

The latter, without a party, was until then only a media personality, active mainly on TikTok, spreading messages against Europe, against NATO, against Ukraine, against vaccines, against the alleged ‘globalist conspiracy’ against traditional Christian society and against the ever-present Jewish finance, going so far as to glorify Ion Antonescu, the Romanian dictator who was a controversial ally of Hitler.

Against all odds, it was the two populists who qualified for the second round: Lasconi with about 1,800,000 votes (19%) and Georgescu with about 2,100,000 (23%).

The latter figure was a thunderbolt, especially since Georgescu had basically only used TikTok to win his votes. He had not launched any visible electoral campaign, neither by road nor by television. His declared election expenses had been zero.

A week later, on 1 December, parliamentary elections were held. Here Georgescu, not having a party, did not run, and it was minor Eurosceptic forces such as Simion’s that took the spoils, all together reaching around 30%. However, 70% of Romanians, it should be remembered, expressed unequivocal support for parties close to Europe and Ukraine.

The final showdown between Lasconi and Georgescu should have taken place on 8 December. But two days earlier came a Constitutional Court ruling that is unprecedented in history: the first round will have to be repeated because it was not played on equal terms.

A few hours later, a wave of searches and arrests swept through Bogdan Peshir, the billionaire who was allegedly Georgescu’s occult financier, Horaţiu Potra, the head of a mercenary company that took care of his private security, and some members of neo-Nazi groups that supported him.

Georgescu immediately cried ‘EU and NATO coup’, while his challenger Lasconi thundered against the violation of the will of the people.

For the sake of completeness, it must be said that the polls were divided between those that gave Georgescu a large favourite and those that gave Lasconi a win at home even if he lost among Romanians in the diaspora.

But what were the reasons for this shock sentence?

The judgment

The nine judges had unanimously found three flaws in the first round of the elections, in the wake of an intelligence report that has been publicly available for a few days.

The vice that all the foreign newspapers have been talking about, i.e. Russia’s probable direction behind the Georgescu operation, is actually the last and least relevant.

The objective problems were two others. First: Georgescu’s funding was not transparent. Second: TikTok and other platforms constitutively favoured Georgescu over the other candidates.

What happened, in the last days before 25 November, was the awakening of an organised network via Telegram and at least 35,000 fake profiles on TikTok, which, with the help of more than one million euros spent by Peshir on the latter social network, produced 52 million views of Georgescu’s videos in just four days.

This media offensive was enough to divert hundreds of thousands of votes from Simion and abstention to Georgescu, propelling him to the ballot.

Now, the question arises: could it not be simple skill in the use of a media?

Why are the Romanian judges so sure that TikTok behaved with Georgescu as the mainstream media behave in dictatorships, offering him a preferential channel and drugging the electoral competition?

How TikTok works

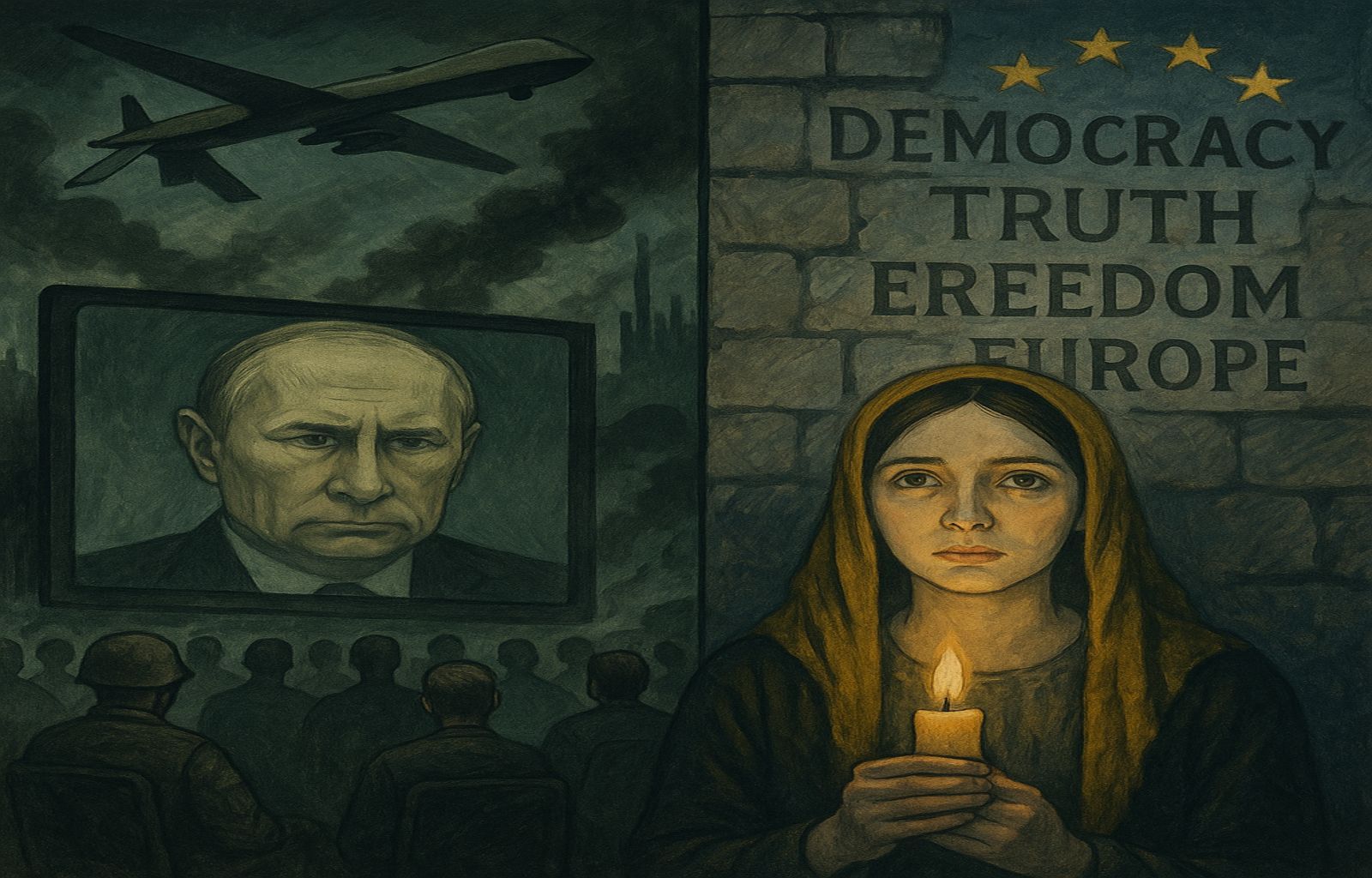

It has been known for years that TikTok, a company whose majority shareholder is the Chinese state, has an algorithm that intentionally promotes content in line with the Beijing regime’s agenda. Anything that can discredit the European Union or the so-called ‘Western’ democracies is therefore rewarded in views, and vice versa.

Any user of TikTok, for example, no matter how he or she thinks, can confirm that it is almost impossible to find pro-Ukrainian or pro-Israeli content there, as it is shadowbaned: not deleted, but simply curbed in its circulation.

Let us bear in mind that TikTok is now no longer the social ‘of kids’ and ‘of ten-second dances’, but a real portable television, offering mainly medium-length videos.

In fact, therefore, millions of Europeans and Americans of all ages have in their pockets a TV controlled by a hostile regime, without any filter or par condicio. This is, by the way, the reason why the US judiciary, in recent months, has deemed it a threat to national security and permanently ordered ByteDance (the American branch of TikTok) to find an American owner or close up shop.

In Romania, however, the problem was not just this ‘invisible hand’ inside TikTok’s algorithm, but a series of improprieties carried out in the light of day.

Georgescu, for example, was not labelled as a political candidate (which in fact, until a few days before, he was not) and did not have to suffer the restrictions on video virality that profiles of political candidates normally suffer. In short, there was at least one (very powerful) medium where the competition was not a level playing field.

Too big to fail

Those who speak of a ‘coup’ are, of course, exaggerating: if these elections, once repeated, led to the same result, they would not be ‘cancelled indefinitely until the right one wins‘ (cit.).

But many liberal commentators, Lasconi in the lead, have also accused the Romanian institutions of excessive self-defence.

Indeed, in the long history of social interference in electoral processes, such drastic intervention had never been seen. In any democratic country, until now, when faced with such cases, independent authorities and moderate politicians had competed in displaying a kind of sportsmanship or refinement: ‘People have expressed a sentiment that should be taken into account‘, ‘Votes should be respected anyway‘, ‘Social media are not the problem but only the expression of the problem‘, and so on.

In practice, they were admitting that electoral consensus retrospectively justifies any abuse committed to win it. As if there were a mystical ‘voice of the people’ just waiting to be revealed and, once revealed, make all those counterweights that could have silenced it appear illegitimate. A logic, in short, according to which Matteotti and the Watergate journalists would have been enemies of democracy.

Even moderate European politics, therefore, was espousing the Jacobin ideal of totalitarian democracy, where he who ’embodies the needs of the people’ (and not even the majority of them!) has the right to impose himself at all times and at any cost. The same ideal, incidentally, that has allowed the Erdogan, Putin, Orbán, Lukashenko and Ivanishvili to never again relinquish power after conquering it the first time around.

What was different this time?

First, the speed: Georgescu’s rise took place in just two weeks, with a surge in the last four days, and no one had any plans on how to react.

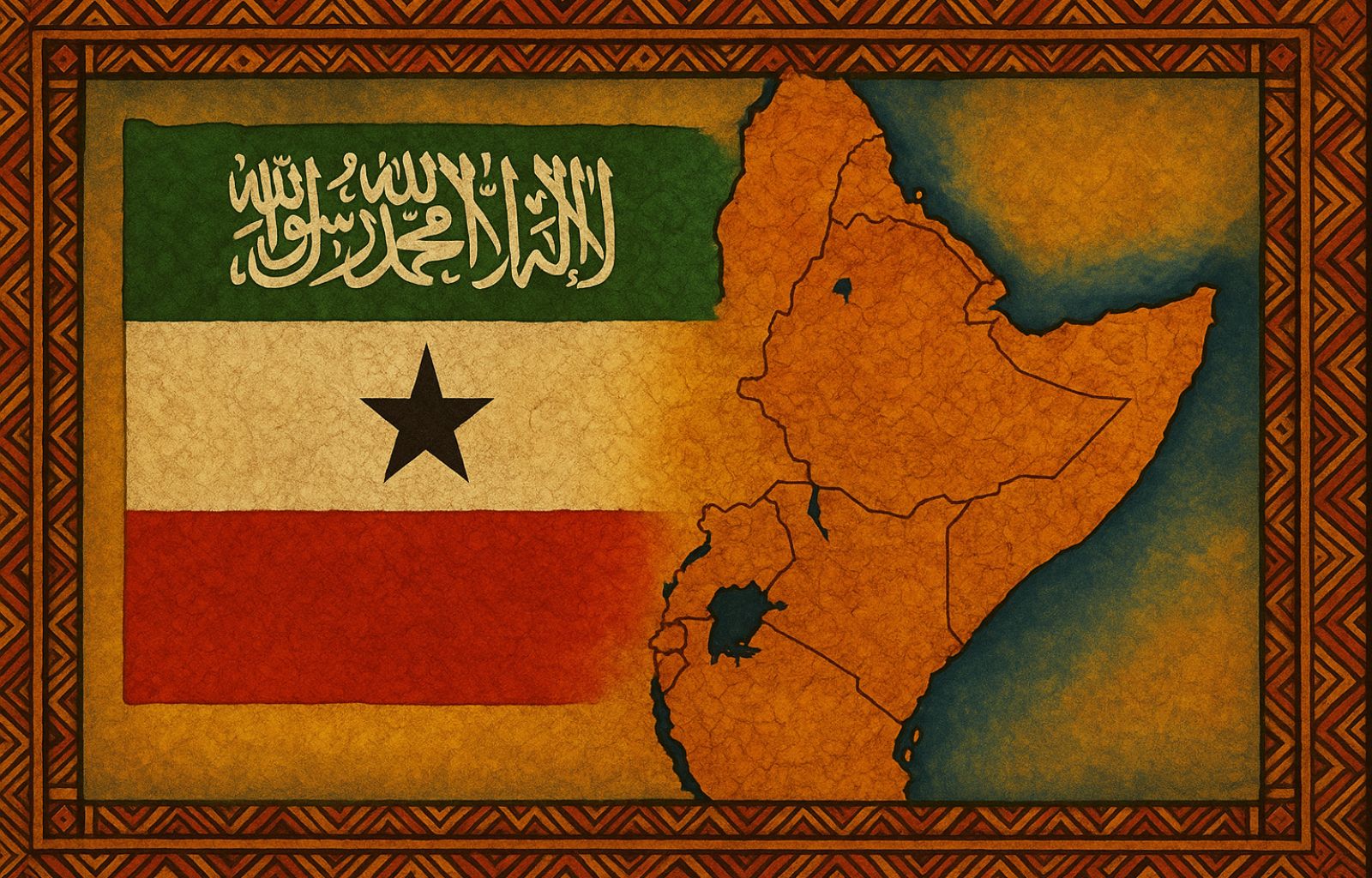

Then there is the military context: Romania has Ukraine’s back, and a disengagement would have been fatal for the latter.

Moreover, the violations of the laws on transparency and equal opportunities among candidates are blatant and demonstrable.

Finally, as the vote for parliament made clear, Georgescu’s greater popularity compared to Lasconi (described by the Russian bots as ‘a hysterical kindergarten teacher with a lesbian daughter‘) does not imply any desire on the part of Romanians to leave the EU or NATO.

It was probably these reasons that convinced the court to abandon all feigned sportsmanship and enter the penalty area.

If we want to look for an Italian precedent, something similar happened to when Mattarella refused to appoint Savona as economics minister in the first Conte government: the president was able to force his hand because he knew that the vote for the Lega and Cinquestelle did not amount to a mandate to leave the euro. In that case too, as you will remember, there were cries of a coup and the death of democracy. In that case too, as you will remember, the squares remained empty, impeachment was only in Di Maio’s dreams, and Italian democracy went on its way.

What now?

In Romania it could end in a thousand ways: even, I repeat, with the actual victory of Georgescu, who would, however, find waiting for him a parliamentary coalition already formed with a government programme ready and opposite to his own.

The events in Bucharest, however, are indeed a ‘dangerous precedent’ with regard to relations with TikTok: what will the other European states do, all the more so knowing that the United States has also chosen strong-arm tactics ?

And how to assess whether other social media are equally distorting during election campaigns?

How legitimate is it, for example, to sink TikTok while keeping afloat X (the old Twitter) that favours Trumpian content? In this case, foreign ownership risks really being the only discriminator.

Looking ahead to the next few years, then, politically aligned artificial intelligence chatbots will inevitably be born, with which people will be able to converse, having reality explained to them only from their point of view, and eventually becoming increasingly radicalised.(Mussolini’s, albeit satirical, already exists).

How is it even conceivable to maintain ‘equal opportunities’ and ‘fair competition’ in such a chaos?