For an open secret, Nordio gave Abedini a victim’s licence

It could be said that Minister Carlo Nordio yesterday simply finalised the prisoner exchange agreed between the Italian and Iranian governments following the release of Cecilia Sala. But those who would say that would be very wrong.

The gift of political absolution

Nordio has done something much more and worse, reciprocating the ‘gift’ of Cecilia Sala’s early release from prison with respect to that of Mohammad Abedini Najafabadi – to protect the open secret of the exchange and preserve the formal independence between the two events – with the ‘gift’ of a real political acquittal of the Iranian engineer accused of terrorism offences.

It could be said that Nordio had no alternative and that in order to resolve the matter quickly, without waiting too long and jeopardising the freedom and safety of the hundreds of Italians living in Iran, he could only justify his choice as he did, i.e. by reviewing the validity of the charges against Abedini and declaring that “no element has so far been put forward as a basis for the accusations made, as only the production and trade with his country of technological instruments with potential, but not exclusive, military applications has emerged with certainty, through companies traceable to him”.

But those who would say so – and almost everyone says so – would be wrong again.

Was a motivation from Nordio necessary? No

When extradition is requested (Article 697 et seq. of the Code of Criminal Procedure), the Minister may exercise his power either by not granting it at the end of the judicial process of the proceedings, or – as in this case – by revoking the restrictive measure (Article 718 of the Criminal Code), when it has been ordered, and thus immediately restoring the freedom of the person arrested at the request of a third country.

In both cases, the Minister’s decision is entirely political in nature; in fact, it is the Code of Criminal Procedure that provides that the Minister of Justice may not grant ‘the extradition request when it may jeopardise the sovereignty, security or other essential interests of the State‘ or ‘taking into account the seriousness of the offence, the relevance of the interests affected by the offence and the personal circumstances of the person concerned‘ (Article 697, paragraphs 1-bs and 1-ter of the Code of Criminal Procedure).

Therefore, in order to release Abedini Nordio did not at all need to take the place of the judges who were dealing with his case and pronounce a political acquittal para-sentence, which was neither due nor required and became a kind of gratuity that the government added to the price agreed with the Iranian authorities.

Why has the government been so generous to Tehran?

Because to the exchange of prisoners was added a further political exchange, that of the dissimulation of the quid pro quo between Abedini and Sala in the form of a gratuitous correspondence of courtesies between Iran and Italy, in the name of mutual understanding and reassurance. Nordio not only freed Abedini. He also gave him a victim’s licence, as long as Tehran held up the game of ‘there was no exchange’.

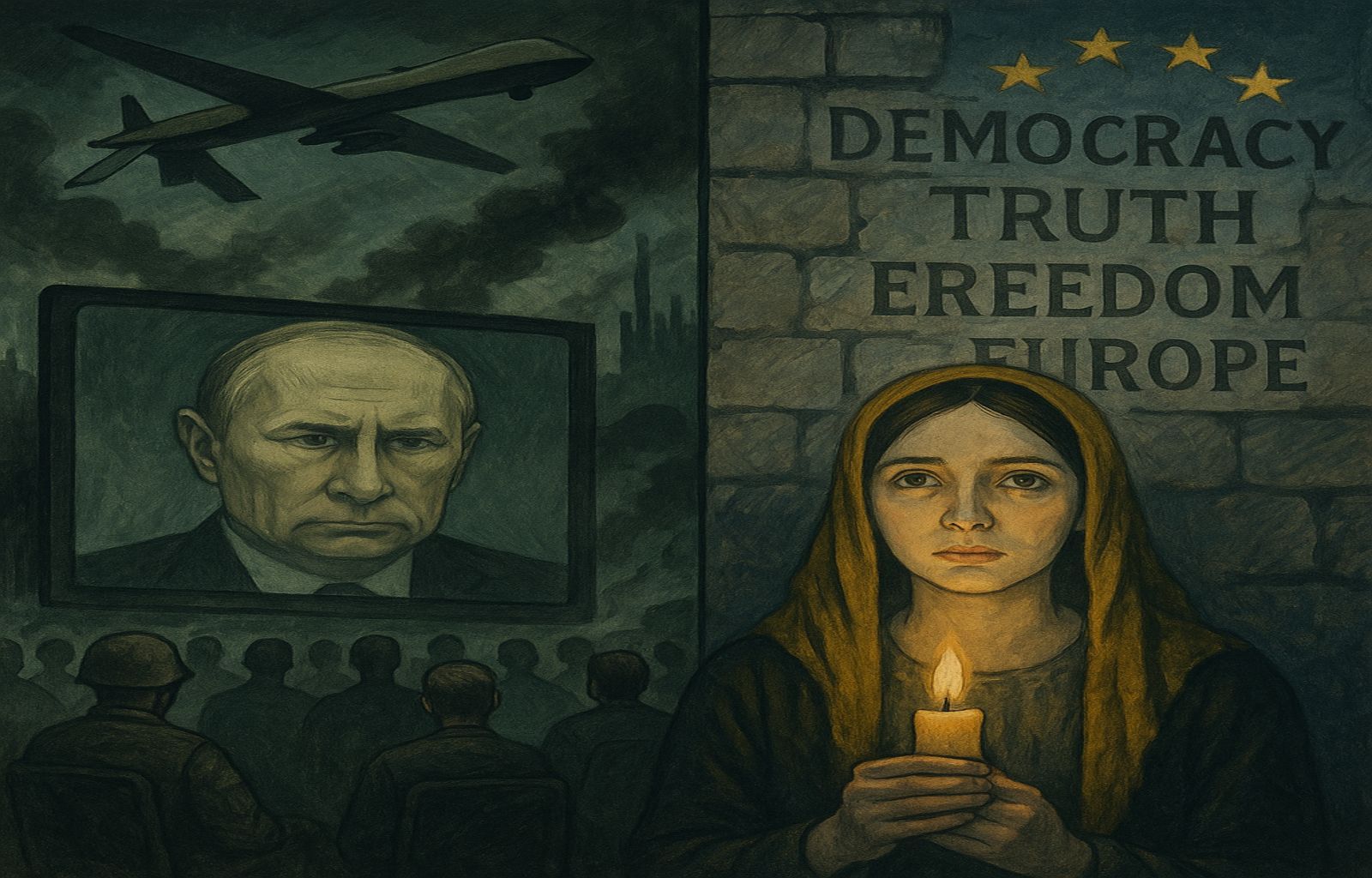

All democratic countries negotiate exchanges such as the one we are talking about, precisely because they assign a value to human life and freedom that is enormously higher than the value that tyrannies assign to men and women subjected to their power. The higher value of life in a free country makes the price of their citizens’ freedom higher and thus the blackmailers’ profit higher. In 2011, in order to free IDF Corporal Gilad Shalit, Israel agreed to release more than a thousand Palestinian prisoners, even those convicted of very serious crimes (among them Yahya Sinwar, who would shortly become the military leader of Hamas).

There is therefore nothing to censure or object to in the Italian government’s decision to give in to this blackmail, not least because a country’s weakness and blackmailability do not depend on its greater or lesser willingness to pay a price for the freedom of its citizens, but rather on its resolve to subsequently make its citizens pay a very high price for the arrogance of the kidnappers.

Instead, the government, by choosing to acquit Abedini and to give Iran a precious platform for delegitimising the investigations into the Pasdaran’s transnational terrorism, has done the exact opposite: it has declared itself to be a country at Tehran’s disposal and has demonstrated for the umpteenth time that Italy’s “open channels” with countries “whose policies and actions it does not share” – as claimed by Foreign Minister Tajani – remain under the banner of a far from reassuring political duplicity.