Sister of Europe? The Melonian paradox

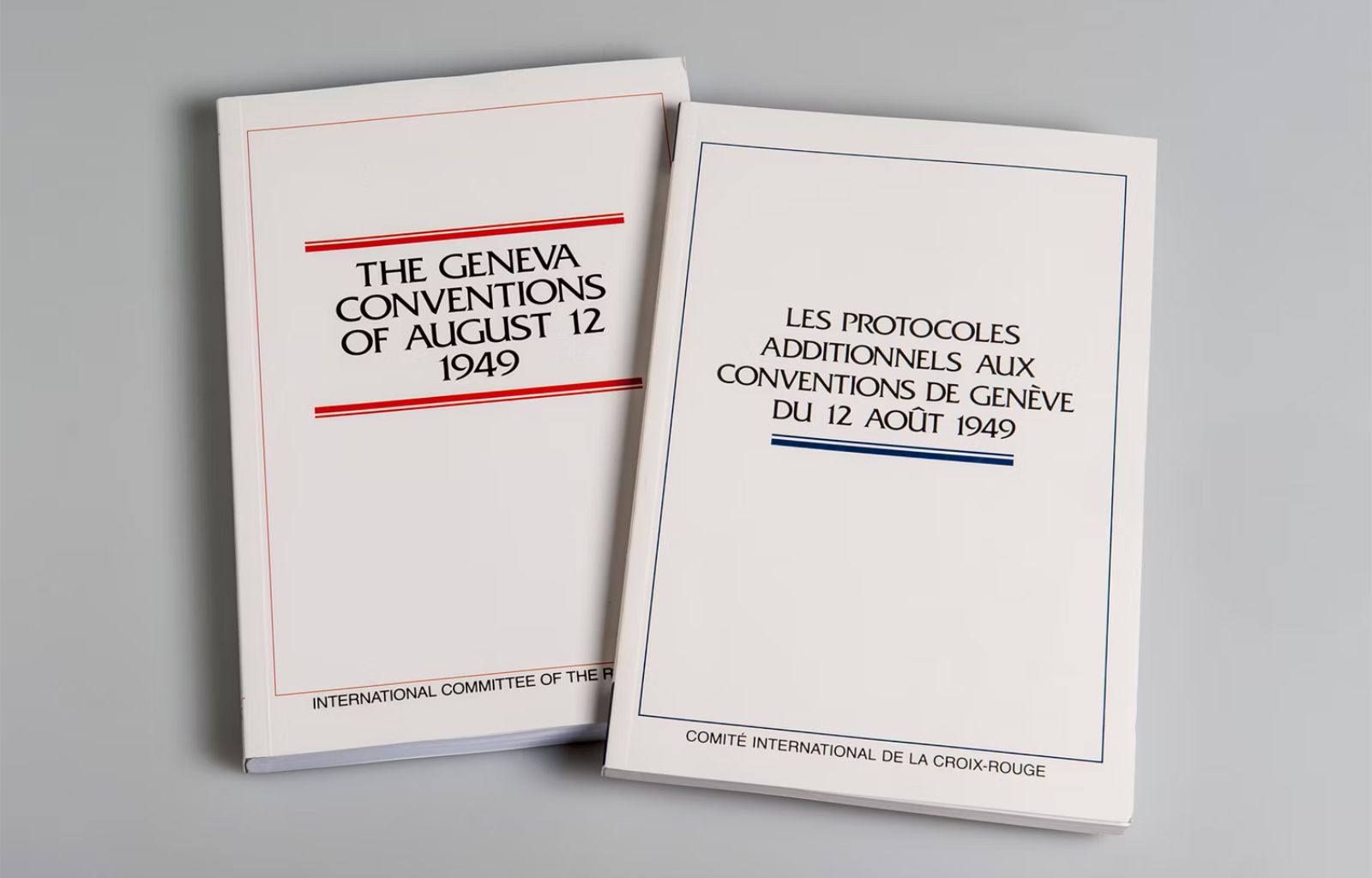

It is now a fact that the new Trump is more and more similar to the very old Trump, the unscrupulous real estate developer who, with an aggressive and engulfing attitude, acquired New York neighbourhoods yesterday, increasing his fortune. A very different Trump from the one in his first term, strengthened by a re-election after the events on Capitol Hill, also winning the popular vote that made him, in his conviction, invincible. And precisely with the unscrupulousness of the very first Donald, he has reappeared on the world stage, candidly announcing that he wants to acquire territories and raw materials in defiance of any rule of international law and the principle of peaceful coexistence.

After all, it all comes back to Trump-thinking: why hold the US anchored to the principles, values and customs that have made it the leader of the free West, when its major competitors then act undisturbed, free of the checks and balances that characterise liberal democracies, even more so when those values don’t feel like your own?

For Trump there is only one binomial: the purely economic one of costs and benefits, in which the former must be minimised in order to maximise the latter. Here it is that rehabilitating Putin, inviting him to Washington and actually letting him win the war, if from a political, ethical and liberal values point of view it represents a very high cost, the very negation of those principles, from the Trumpian economic point of view, which does not see those principles as monetisable, is a derisory cost compared to the enormous benefits of a peace imposed on Ukraine – on Putin’s terms alone – by stripping it of its raw materials. So it is with Gaza, where the announced deportation of an entire people and the invasion of a territory are well worth a US Mediterranean colony in which to build dozens of Mar-a-Lago.

The new Yalta: Trump plays Risk with the globe

This is Trump: the exaltation of pragmatic cynicism, a Machiavellian prince in Super Saiyan version for whom any means justifies any end. For him, Putin could take all of Ukraine and even a chunk of the European Union while he occupies Greenland and conquers Canada, perhaps allowing himself a moment of distraction just to allow Xi to invade Taiwan, while the Marines take control of Panama. In his mind there is a new Yalta in which he, Putin, and perhaps Xi sit down at the table to divide up the world, starting with Europe, which has been reduced to its lowest ebb and internally disintegrated thanks to the metastatic action of schizophrenic and probably well-subsidised European sovereignists, more devoted to vassalage than patriotism.

And he is wrong who counts Giorgia Meloni among these sovereignist sketches. Not because the Premier does not have a proudly ostentatious patriotic-sovereignist curriculum, indeed precisely because of that, because hers is the personal story of a political community that has grown up remaining faithful to the principles and values that have inspired it, staying on the fringes and having the ability to get out of comfortable logics that would have given her and her group every chance of a fast political career fifteen years in advance.

The paradox: Giorgia Meloni as antidote to Trumpism

It is not a question of whether or not we share the principles and values that inspire the day-to-day and ordinary activities of the government led by Giorgia Meloni, but we must take note that today Giorgia Meloni is one of the few, if not the only, European leader who, from the right, can stem the Trumpisation of Europe.

Giorgia Meloni’s right wing is not a right wing prone to the allure of imperialism, but a communitarian right wing that resents the idea of making Italy and Europe into Chinese, Russian or American colonies; it is a right wing that celebrates the fall of the Berlin Wall as a crucial moment for theunion of European peoples; a community that is inspired by Jan Palach and that knew what Bloody Sunday was long before Bono and U2 made it a hit; a right-wing that also counts among its ranks many supporters of the cause of the Palestinian people and, for this reason, does not assume anti-Semitic connotations. In short, a right wing that has firmly in its DNA its own code of values that is difficult to sacrifice on the altar of political and personal expediency.

In the panorama of the non-traditionally liberal European right, Giorgia Meloni is the only credible leader, the only one who has taken and maintained an Atlanticist line (even if by now the concept of Atlanticism will have to be revised) and firmly pro-European, albeit with a different idea of Europe from the current one, but nonetheless of a Europe that is a protagonist and not disintegrated, light years away from the idea of the ‘patriots’ gathered in Madrid who, contrary to the propagandized Make Europe Great Again, work like useful idiots for a Europe reduced to nation-states, colonies under the influence of the superpower of the day.

This is why today Giorgia Meloni finds herself, paradoxically, both the closest European right-wing leader to Trump (and Musk), but also, in power, the greatest antidote to Trumpism that risks irreversibly contaminating the old continent. That is why today it is crucial that on her foreign policy line, the line of a liberal democracy, in this very Finnian, she receives support and help from the opposition when it comes to defusing attempts at sabotage within the majority, just as she did with Mario Draghi, helping him to confront the continuous attempts at sabotage always made by the same internal agent – the same one, unique among all, who kept silent in the face of Russia’s despicable attack on President Mattarella.

The rest is everyday domestic politics, confrontation and clash over economic recipes and distinct and distant visions of society on which voters will have to choose, knowing however that on the country’s European and international positioning, apart from the usual collaborationist, the position is and will remain firm.