Defence, peace, Europe: Schlein is unfit to govern

International politics is the litmus test of political leadership. And it is precisely on international politics that PD secretary Elly Schlein is demonstrating her total inadequacy, which in our opinion makes both her and her PD unserviceable as a government option for Italy. Her latest sortie – a hard ‘no‘ to the European defence plan proposed by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen – has certainly made part of the Democratic Party uncomfortable, starting with the so-called reformists, but it is no surprise to those who have long grasped the inconsistency of the political line of the current leader of the main opposition party.

Anyone who wants to take the trouble to look up Schlein’s past statements on European defence will always find her entrenched behind ‘yes, but‘ and behind a particularly hypocritical thesis: the illusion, peddled to the electorate and useful to their own ideological scaffolding, that common European defence will save money compared to current national defence spending.

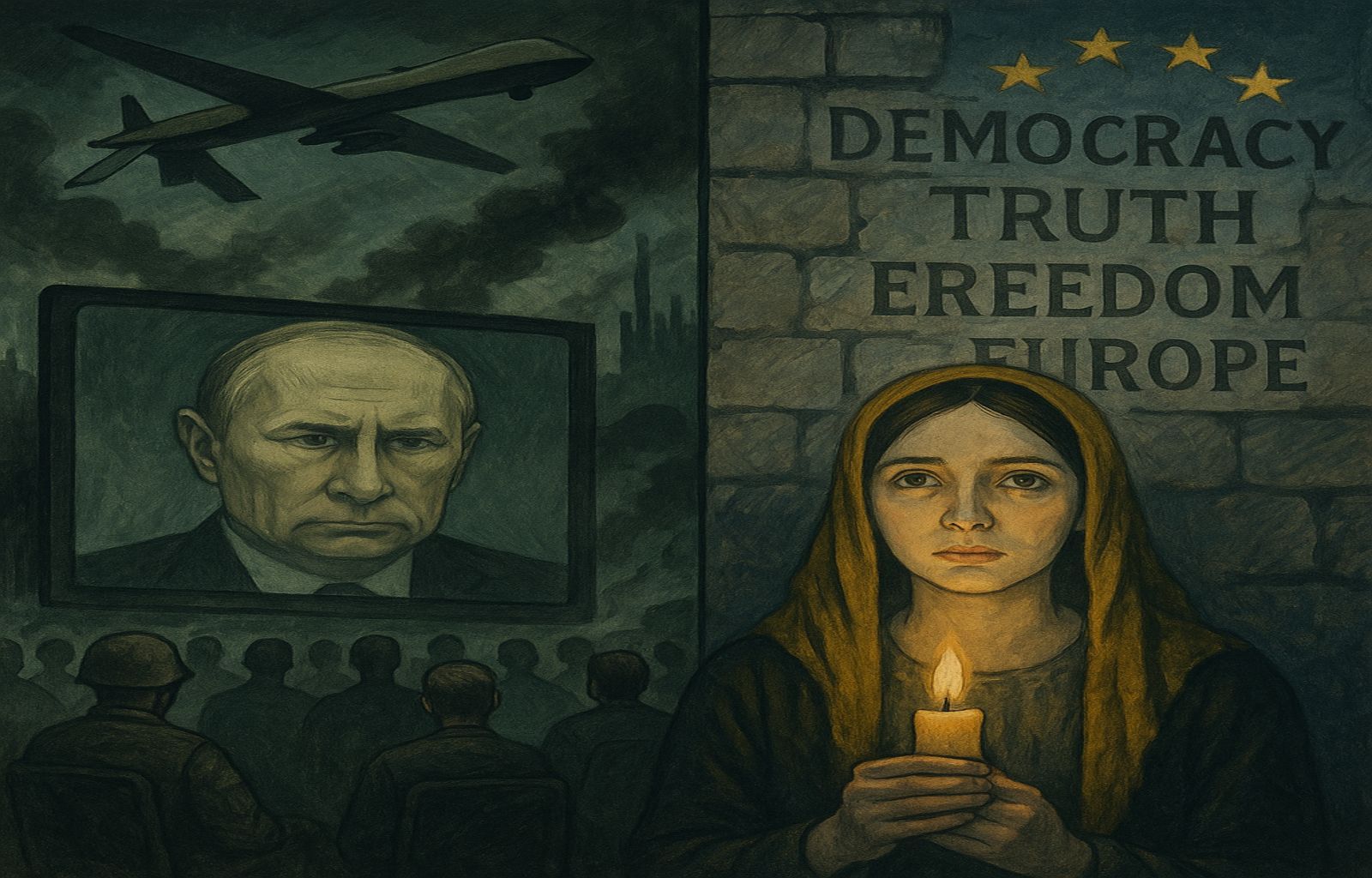

This is quite different from saying, as is possible, that at the same level of expenditure, the merging of national armies into a single European army generates savings and greater efficiency. But it is, on the other hand, clear to those who have moved beyond the high-school dimension of politics that Europe, in one way or another, must invest much more heavily in its own security. And it must do so today, because the threat to our freedom is right in front of us.

The unbearable argument used by Schlein is the opposition between ‘national rearmament’ and ‘common defence’. The Pd secretary has raised aprioristic barricades while forgetting a fact: even we unabashed pro-Europeans know that the realisation of a common European army is a medium- to long-term goal, an objective that requires a common foreign and defence policy – democratically legitimised – and a definition of the issue of issues, the sharing of the governance of French nuclear deterrence. To pretend that this process can come into being overnight is a simplification that ends up playing into the hands of those who, like Giuseppe Conte or Matteo Salvini, are shamelessly siding with an irresponsible, anti-patriotic, anti-European pacifism.

This is where Schlein’s political fragility and inadequacy are revealed: instead of presenting herself as a responsible and authoritative leader within the Union, capable of negotiating with Brussels to make defence investments more effective and sustainable, or perhaps to link them to concrete steps on the common defence governance front, she prefers to chase after Giuseppe Conte on his turf, more interested in defending the borders of the fu fu campo largo than of Europe. Concerns about the risk of using cohesion funds earmarked for social policies also seem puerile in the geopolitical framework we are currently experiencing. It wouldn’t take much imagination, for example, to enhance this choice by asking for guarantees that these resources will be used to promote the retraining towards the defence industry of workers in the automotive sector today under pressure due to the heavy crisis in the sector. But to make such reflections, one needs to have overcome the dream dimension of high school politics.

Today Mario Lavia in Linkiesta points out a worrying fact: if Schlein’s position really coincided with that of the Democratic Party delegation to the European Parliament, von der Leyen’s majority would already be compromised. The more pragmatic in the PD, such as Lorenzo Guerini, have tried to shift the centre of gravity of the debate on the possible improvements to be made to the Commission’s proposal, and fortunately the Dem delegation in the Strasbourg hemicycle counts figures such as Pina Picierno, Maria Elisabetta Gualmini, Irene Tinagli and Giorgio Gori who – barring surprises – should at least ensure that a part of the votes available to the PD will be in support of the Commission. But the political problem remains, as big as a house renovated with the superbonus.

To brand as ‘national rearmament’ a historic attempt by the European Commission to change the paradigm of European construction, definitively overcoming the purely commercial dimension of the European integration process, means for Schlein to have attended the European institutions in vain. Worse: it means dragging the PD and the entire centre-left into the anti-European drift of those who contest Brussels on principle, and risks bringing more water to the mill of the sovereignists and pro-Putinites who have now infiltrated Italian politics.

What Schlein does not want to see, whether out of tactics or incompetence, is that the Commission’s proposal charts a course from which there will be no easy return and which will mark, functionally, the birth of European defence: the provision of €150 billion from the EU and the opening of the loopholes for total expenditure in national budgets of up to €650 billion will not be left to the mere discretion of national governments, but will inevitably be framed within single rules for procurement and purchasing methods, just as it will be a powerful drive towards aggregation and ever greater integration of the European defence industry. Ever since the days of the ECSC and Euratom (by the way, what does the PD think about a return to nuclear power?), the European Union has been born out of concrete things. And it is time to return to that spirit.