Dugin, Rauti, Hezbollah and cribs: notes on a right-wing that does not change

Aleksandr Dugin, the Russian philosopher considered by many to be the ideologue of Putin’s geopolitical vision, considers European civilisation to be by now collapsed; his words, published in the latest issue of Millennium, a monthly magazine edited by Peter Gomez, are lapidary. Dugin, with his prophetic and edgy style, re-proposes the cornerstones of his thinking: the crisis of Western liberalism, the end of American-led unipolarism and the emergence of a multipolar order based on alternative civil, religious and geopolitical identities. In this context, he presents thecurrent liberal democratic order as a decadent, nihilistic, soullessconstruct based on the cult of the individual and American hegemony. An order to be overthrown.

At the centre of his analysis, the figure of Donald Trump is extolled as a subversive force that has broken the spell of globalisation. The US President is described as the illiberal battering ram who has challenged the foundations of the ‘post-Cold War world’. However, Dugin, with pragmatism, does not limit himself to a benevolent narrative towards Western ‘sovereignist’ movements: many populists, according to the philosopher, once in power ‘adapt’ and lose their revolutionary force. It is here that Dugin mentions Giorgia Meloni: the Prime Minister would be yet another demonstration of how the ‘anti-modern’ revolution is often defused by the attainment of power. To use a terminology dear to the Italian right, ‘a Ring to tame them, a Ring to find them, a Ring to ghermirirli and in the dark chain them’.

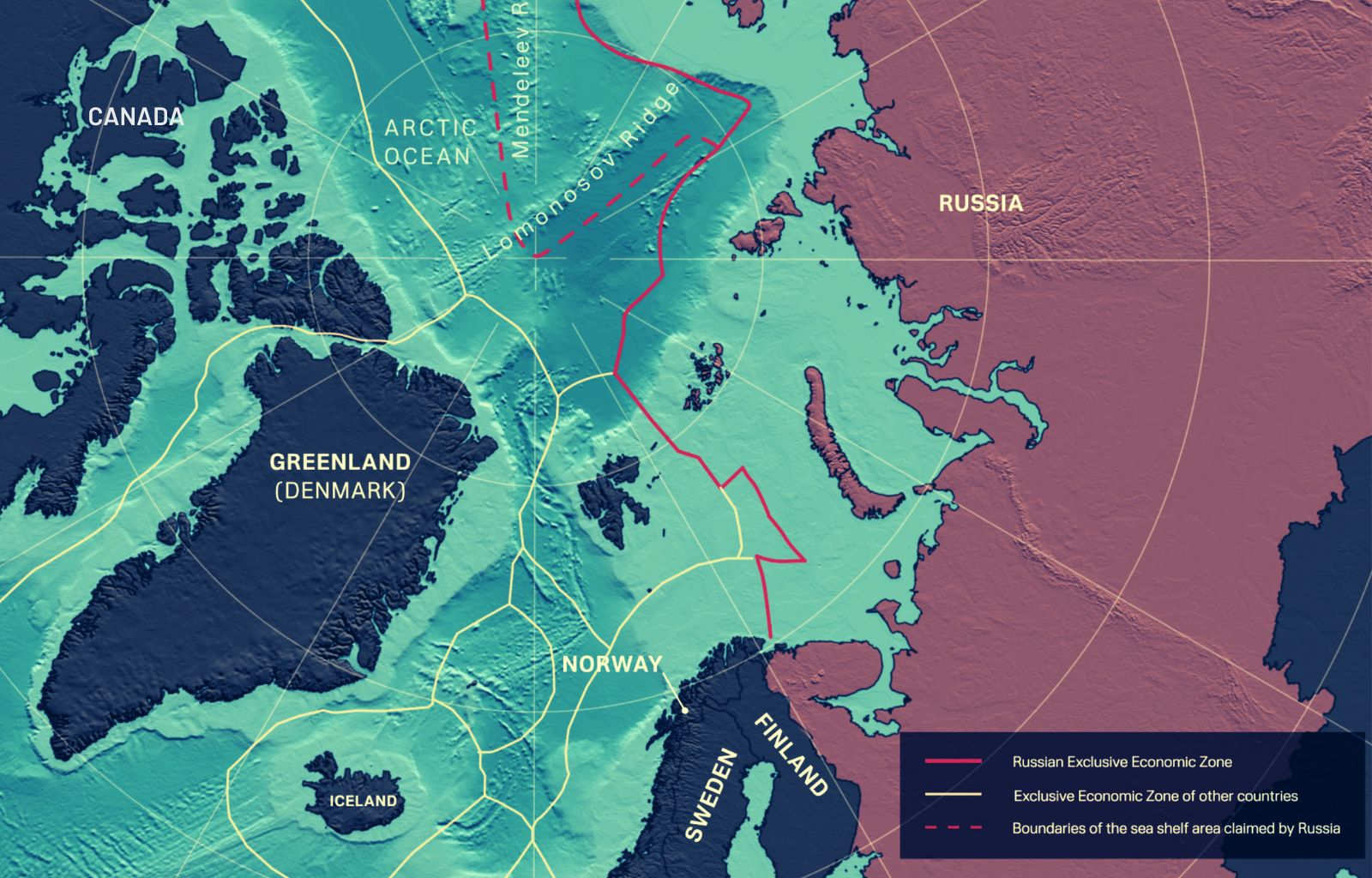

Yet, Dugin takes a close look at Italy. Our state has a significant weight in the European Union’s hold. For Moscow, Italy can be a junction, an entry point into the fault lines of the West. For this reason too, its mistrust of Meloni is accompanied by constant interest.

The Right’s fascination with Pino Rauti, champion of anti-modernity

If a Martian were to descend to Earth today and observe the Meloni government, he might think that there is no connection between Italy and Dugin: in fact, Italy’s current international choices are aligned with the European Union and there is no striking break with past governments. And yet, it is enough to turn back the hands of a few years to find statements that are very much out of line with the Atlanticism now flaunted by the Prime Minister: Suffice it to mention those of Giorgia Meloni (“if in Syria it is still possible to make cribs, if it is still possible to defend the Christian community, it is also thanks to the Hezbollah militias”), those of Paola Frassinetti on Iran (“Islamic terrorism is notoriously financed by Saudi Arabia and its satellite states, Iran, on the contrary, fights it”) and even the tribute of National Youth to the Iranian General Qassem Soleimani, Commander of the Pasdaran Quds forces. Certain orientations did not originate with Dugin. They come from much further back. One need only think of Pino Rauti, celebrated by not a few exponents of the current centre-right majority. A key figure of the post-war Italian right, founder of Ordine Nuovo and then Secretary, for a few years, of the MSI, Rauti did not join Alleanza Nazionale and refused Fiuggi, but his ideas – spiritualism, the third way, breakthrough to the left, anti-Americanism – live on even in those who formally accepted those turns. Influenced by Julius Evola, Rauti imagined a mystical, revolutionary, communitarian Right. He saw modernity as disintegration and sought alternative models in the Third World, in Arab populisms and identity movements; not by chance, we can also find similar themes in the words of Mohammed Ben Abbes, the Arab-French President in Houellebecq’s novel ‘Submission’. There is a red thread that binds the hostile forces in our world, a red thread that must be known and that cannot be trivialised in the Italian bipolarism that by now sounds more and more like a play out of time.

Gianfranco Fini and the dream of a Europeanist, modern, liberal right wing

It is surprising how much of that language survives in the militant and youth base of Fratelli d’Italia. This is the crucial point: the greatest fault of the new generation of Fratelli d’Italia, and in particular of Gioventù Nazionale, is that they have never really made the Fiuggi path their own. A path that, at least in Gianfranco Fini’s vision, was clear: Europeanism, proximity to Israel and modernisation. Fini, in my opinion, was sincere and took risks himself. In his political life he may or may not have liked it, but it is clear that he was always willing to go beyond merely administering the existing; on the contrary, Gianfranco Fini often had the desire and the ability to make countercultural and risky turns, paying the price. Unfortunately, today we have a militant base that has only formally accepted those turns out of necessity and continues to feed on symbols, language and content worthy of the most repetitive reductivism. We could cite, ex multis, the now famous Fanpage investigation into National Youth or Maurizio Marrone who accused the European Union of carrying out a ‘coup’ in Donbass.

Without all this post-MSI rhetoric, without ideological undercurrents and nostalgic cosplay, would Fratelli d’Italia still have a living youth group? The answer is not obvious. Gioventù Nazionale today seems more tied to self-celebration than to project, repeating 30-year-old slogans and not elaborating a real political proposal. It is an eternal return to nowhere.

We cannot accept that Dugin dictates the boundaries of conservative thought. His trap consists precisely in wanting to convince us that there is only one alternative model to decadence: that of the spiritual and warrior Russia. This is not the case. There is a European tradition that has been able to combine values, conservatism and human rights. A vision in which identity is not incompatible with the dignity of the individual. On the other hand, it is not known how Dugin’s spiritualism, which seems to ignore the divine image present in every human being, is concretely expressed. The war in Ukraine replicated Soviet logic: Putin slaughtered countless human beings in order to create a kind of ‘new world’ without feeling any limits to his actions, effectively denying the idea of God above us.

It is surprising to note how the Right, which has always been attracted by the myth of Europe, seems to be absent at the very moment when the European building site is more open than ever. Or rather: it has stepped aside. Instead of taking up the challenge, young right-wingers repeat the usual ‘politically correct in their desire to be politically incorrect’ phrases and lock themselves in a sterile ritualism akin to tragicomic group therapy. Of course, I am aware that the National Youth guys would reply that they ‘want another Europe’. However, there is one detail that cannot be overlooked: reality is ‘now and now’ and the combination of ‘thought and action’ accepts no excuses. Today is the time for choices: there are those who want to build a strong, solidarity-based and autonomous Europe, and those who prefer to protect their own electoral orchard, perhaps by sheltering behind well-intentioned technicalities, waiting for someone else to take responsibility for the future. The choice, for so many young people, is between being ‘battery chickens’ of a party or really trying to launch a challenge to the stars.