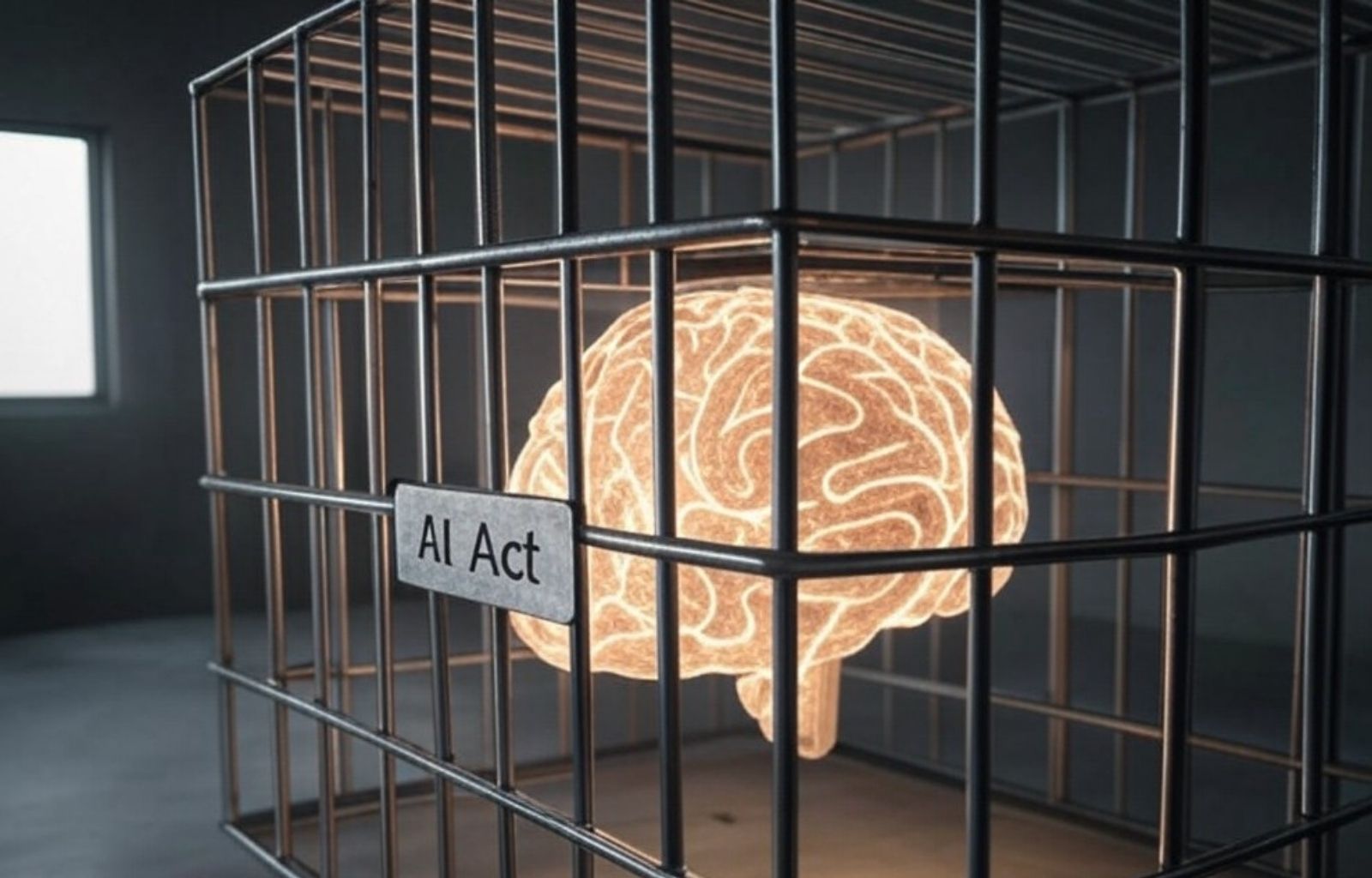

EU should suspend the AI Act, before it is too late

The European Union is shooting itself in the foot. With the AI Act, we risk turning into a stagnant market, where innovation and productivity are stifled by regulations designed to protect, but which end up penalising. And while we impose paralysing constraints on ourselves, under the illusion that we are regulating AI to give it a ‘human face’, the United States (and China) are racing ahead at breakneck speed, investing and leaving the sector deregulated so as not to depress its innovative and revolutionary drive.

The productivity gap is already here

A prime example? Peter Kruger, a brilliant observer of technological issues, offers it to us, relaying on X the launch by OpenAI of Operator, a ‘browser agent’ that automates everyday tasks such as booking a train, reserving a table or filling out a shopping list. A virtual personal assistant that can act as an army of interns at your service, saving hours of time. Operator, however, will not be available in Europe. Why? Because of our suicidal regulations, which make these tools almost inaccessible to EU companies and citizens.

And these are not just tools for personal consumption. “These agents will brutally enter business processes,” writes Kruger, and are set to revolutionise operations management and increase productivity on a large scale. Europe, to date, appears to be out of the game: blocked in access to the most advanced versions of AI models, especially those integrating multimodal functionalities such as images, audio and video.

A future without access to innovation

The effects of the gap are devastating. While the United States can exploit increasingly advanced tools to reduce costs, increase efficiency and create new opportunities, Europe remains stuck in the past. We are not talking about some marginal lag, but about a productivity gap that risks becoming unbridgeable.

European companies are competing in a world where they do not have access to the same tools as their global competitors. The solution? For us, it can only be to suspend the AI Act with immediate effect.

The AI Act is not protecting Europe. On the contrary, it is crippling our chances to compete. Complex and binding rules not only discourage European start-ups, but also make our continent unattractive to global investments. Why should an investor bet on an ecosystem choked by red tape when he can choose to operate in the US or Asia, where there is maximum freedom to innovate?

And there’s more. The AI Act regulations do not take into account the speed with which the industry evolves. In the time it takes to discuss, approve and implement the regulations, the technology will have already leapt forward two or three generations, leaving Europe hopelessly behind.

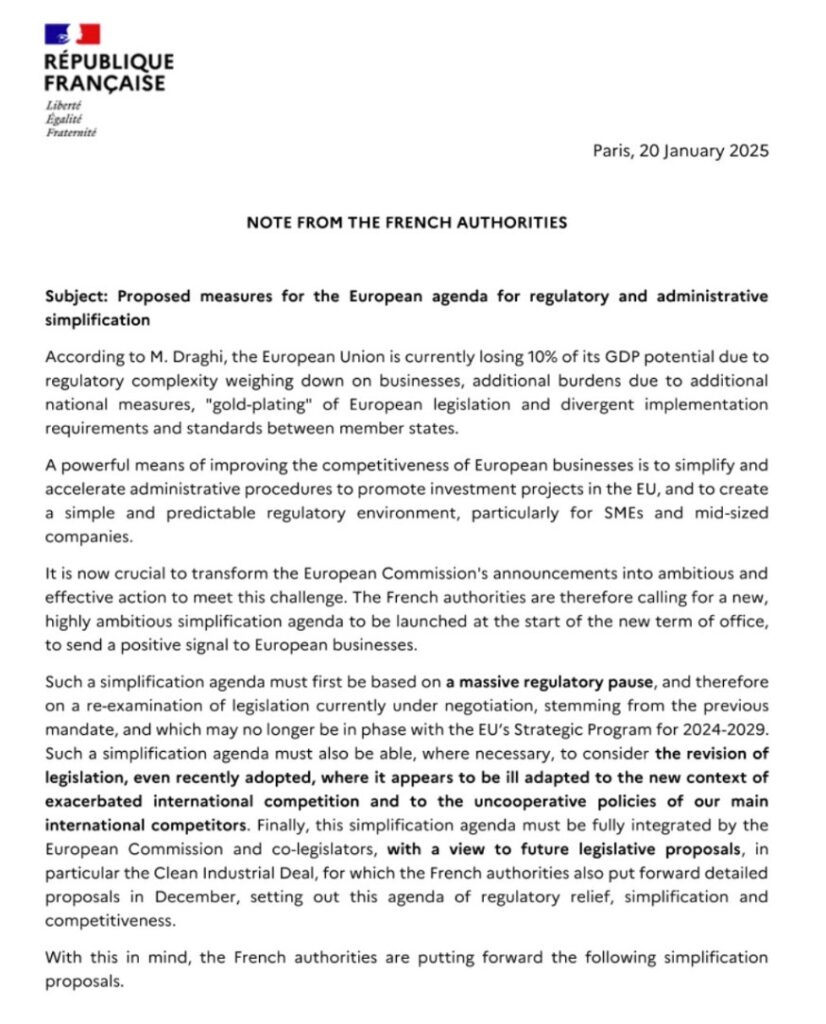

Paris and the informal request for a regulatory break

Even the French authorities are recognising the danger. In a recent document released by Politico.eu, the authorities in Paris – quoting Draghi – point out that EU regulatory complexity costs up to 10% of potential GDP. To address this loss, the paper proposes a simplification agenda that includes a massive regulatory pause and an in-depth review of regulations already adopted or under negotiation, including those related to artificial intelligence.

The French document, in its English version

The new European Commission, at least through the mouth of Ursula von der Leyen, seems to have understood the extent of the problem. But declarations of intent are not enough: concrete actions are needed. And the first thing to do is to immediately suspend the AI Act process in order to rethink it from scratch, with a more pragmatic and innovation-oriented approach.

We cannot afford to miss this historic opportunity. Artificial intelligence is at the heart of global competition in the 21st century. Either we act now, or we risk condemning ourselves to be passive spectators, if not victims, of progress driven by others.

Suspending the AI Act would not be a surrender, but an acknowledgement: just as it was once said that without factories there are no workers’ rights to protect either, today we can say that you cannot delude yourself into regulating something that you do not have and that – precisely by virtue of your regulation – you risk never having.