Europe of reversed Don Quixotes

In Cervantes’ famous novel, Don Quixote was an impoverished little nobleman who, influenced by too much reading, claimed to live as if he had been a knight of ancient times.

“To right all manner of wrongs, and expose himself to all manner of dangers in order to lead himself to a glorious end” was his mission.

“Everything he thought or saw or fantasised, took the form and semblance of the madness that his readings had thickened in his head”: taverns became castles, windmills and wine barrels became giants, and every traveller along the road became an enemy to be faced.

Around him, however, was the real world of 1605. A world populated by shepherds, tavernkeepers, prostitutes, coachmen and barbers, all concerned with minding their own business, earning some money and staying out of trouble.

To save Don Quixote, fortunately, was his squire Sancho Pancia. “A ‘peaceful, well-rested, prudent man, with a wife and children to support and educate‘, who, while admiring his master, patiently tried to bring him back to reality and be the voice of reason: he advised him not to take his oaths too seriously, reminded him that meals must be paid for, warned him of the risk of ending up in prison, and among the many chivalrous tales he was only interested in the one about the filter for curing diseases.

(‘Health spending’, we would say today).

In short, the ‘most beautiful book in the world‘ is so comical, but also so sad, precisely because it portrays the fight for justice and the defiance of danger as the fantasies of a crazy old man, capable of bringing only boredom to a petty and individualistic society.

Now, there are those who obviously saw in Don Quixote the delusions of the ruling class of the declining Spanish Empire, with its delusions of grandeur, its religious exaltation, its sense of honour and its chronic refusal to balance the books.

Once that decline was over, from the 17th century onwards the world would gradually become Sancho Pancia’s, the coachmen’s and the barbers’: the most powerful nations would soon be those where industrious private citizens had the most political clout, starting with Holland and England, the mortal – and never tamed – enemies of imperial Spain.

And so, for generations, we understood the modern West as the land of those ‘peaceful, restful and prudent’ commoners, while medieval values à la Don Quixote evoked the ghosts of a dark age from which the modern West had to emancipate itself.

If sometimes our heart beat for don Quixote, our head always forced us to be Sancho Pancia.

So that, now that the era of Trump and Putin has begun, and in a few weeks the reality we knew has been turned upside down from top to bottom, we find ourselves to be the crazy ones out of reality. This time, however, the tablesare turned.

The world has abruptly become Don Quixote’s, and we insist on dreaming that we stilllive in Sancho Pancia’s.

Let’s look around 360 degrees. America talks of occupying Greenland and annexing Canada, makes deals with the Russian regime to secure Eastern Europe, treats regions and peoples as if they were material resources to be exploited, calls allies ‘parasites’.

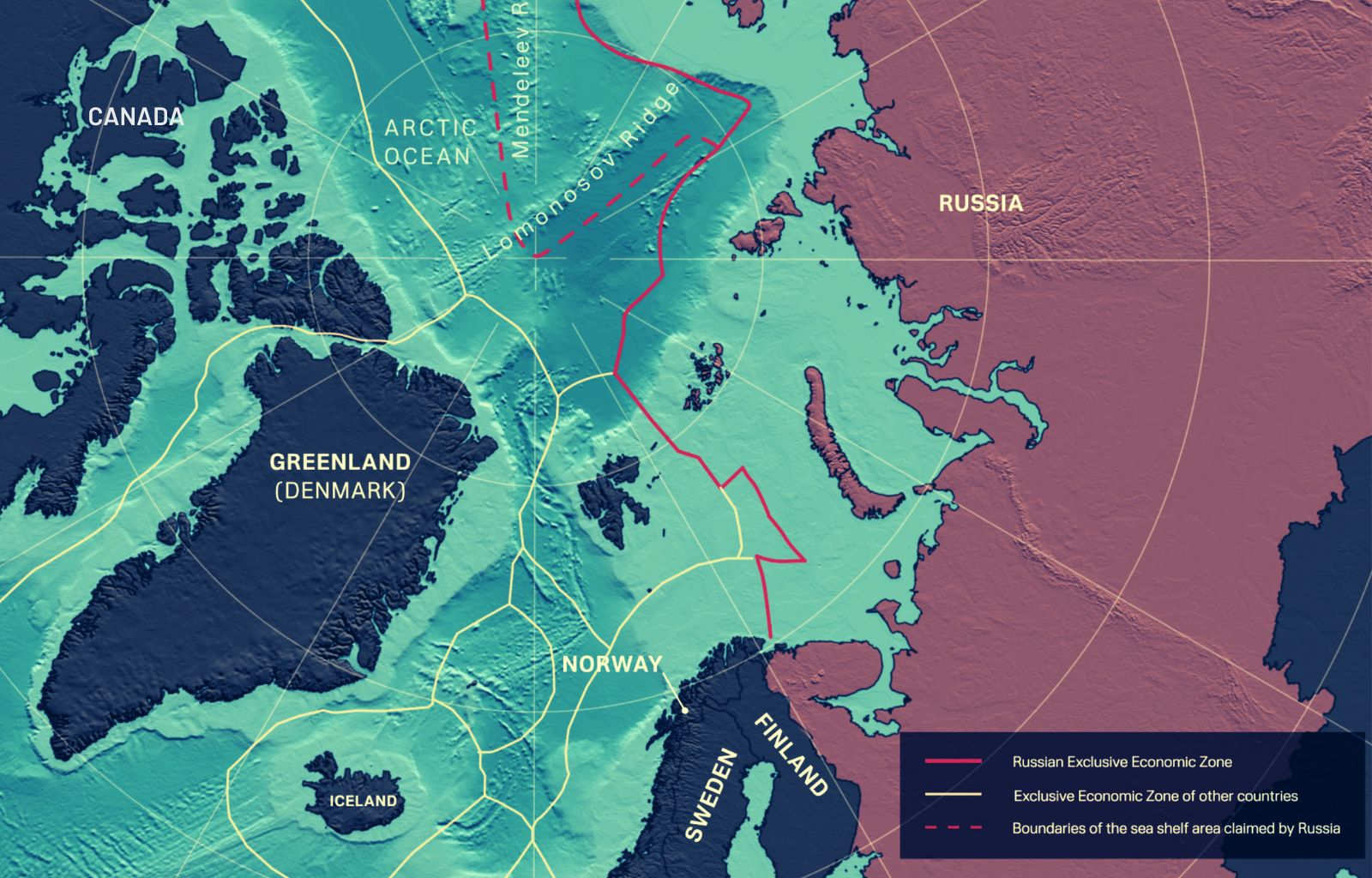

China cuts a European submarine cable every week, carries out continuous military exercises around Taiwan, and is preparing to use an ice-free Arctic to fill the Atlantic with nuclear submarines.

Serbia has resumed its genocidal designs in the Balkans, Erdogan tries to extend Turkish influence throughout the old sultanate, the Sahara is in the grip of coups and civil wars, and the Maghreb is on the brink of a frightening clash between Morocco and Algeria. The Suez Canal is impassable due to Houthi attacks, Israel is hostage to the religious right and the ayatollahs are one step away from producing atomic weapons.

Moral: not even a handkerchief of land or sea on the border with Europe is left where the expansion of an empire is not in progress, either with the weapons of traditional warfare or with the weapons of hybrid warfare (economic blackmail and political infiltration).

These, in short, are not times for ‘peaceful, restful and prudent men’. These are not times of inns and windmills. These are times of castles and giants, and there is nothing crazier than insisting ona harmless windmill where there is a giant tearingus apart alive.

And, not surprisingly, the disinformation agencies in the service of Putin and Trump do everything they can to prolong our stay in a fantasy world of the past, where minding one’s own business only, and having as one’s highest ambition the arrival of a disease filter, was not only legitimate but socially commendable.

Pay attention to the rhetoric of the ‘Putinian uncle at Easter lunch’ or the ‘Trumpian in the checkout line’, who are now the strongest political bloc in almost every western country.

Only a few of them are moved by the identity promises churned out by far-right ideologues like Bannon or Dugin, such as ‘the lack of male authority’, ‘nostalgia for community’, ‘a return to Christian values’.

For the vast majority of them, however, Putinism and Trumpism are simply ‘pure consumer pride’ : the scorn and hatred against any preaching of justice (which in their personal experience has sometimes never existed), the smug relish in sacrificing the greatest abstract freedom in order to have the smallest concrete benefit, the feverish satisfaction of possessing forbidden knowledge that reassures, about the Kremlin’s intentions as well as about the climate trend, the aura of wisdom that emanates from knowing that life has always been only oppression and that Trump and Putin, if nothing else, have the honesty to say so openly.

All these sentiments have a secret purpose: to keep alive that past, now evaporated, where to feel good and to be esteemed it was enough to produce, consume and have a fulfilling private life. The past, then, of Cervantes’ commoners, the Dutch merchants of the 17th century and the westerners of the last eighty years.

A past that, the more it evaporates, the more it is defended and held back, with the force of a desperation that borders on madness: Quixotic madness, to be precise, at the service, however, of Sancho Pancia’s vision of the world.

One only has to look at the hysterical reactions that greeted the release the day before yesterday of the handbook for preparing for the possible outbreak of war. Trivial advice, such as having a medical kit and a power bank at home, which even in the event of earthquakes or floods can make all the difference.

But nothing doing: the ‘Putinian uncle’ and the ‘Trumpian in the checkout queue’ were quick to cry foul, aimed at sowing terror in our families and thus making economic sacrifices more acceptable that in their view would not be necessary.

Someone on X went so far as to speak of ‘tension strategy‘.

For a medical kit and a power bank.

It is ungenerous to get angry at the frenzied tones with which this imaginary world is defended, just as it would have been ungenerous to get angry at Don Quixote for the spear lunges and sword slashes with which he destroyed taverns. These are dangerous phenomena, but they should be viewed with tenderness.

The important thing, however, is to start being serious about these upside-down Don Quixotes’ squires: to remind them that adventures do sometimes happen, that wrongs must sometimes be righted, that keeping one’s word on certain occasions may be important, and above all that children are best ‘maintained and educated’ in a free country, where an adequate number of modern knights prevent invasions and authoritarian twists.