How Poland took off (and now leads Europe)

Economic recovery pillar of rebirth

In a previous article(How Poland is becoming the engine of Europe) we had the opportunity to certify the increasingly central role that Poland is playing in the European political and social context. In this new article we take a closer look at the staggering growth of the country on the Baltic Sea, starting with the lintel on which the ‘people of the Sarmatian plain’ is rebuilding its super-nation: economic solidity.

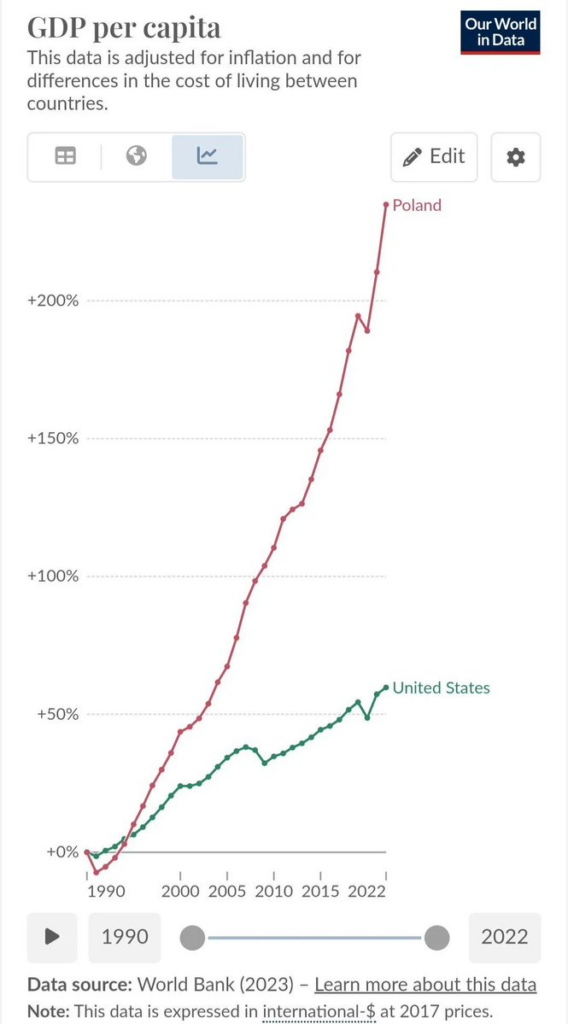

It seems surreal to speak of economic power just 35 years after Poland’s emergence from communist rule and the collectivised economic system, but in the case of Poland, the secret of its rebirth lies in its management of the critical transition between economic models, which has led the nation to become the happy crossroads between Western liberal financial culture and Eastern work ethics.

The smart transition

In the year of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Poland was among the poorest nations on the European continent, battered by more than forty years of USSR control and a comatose, inefficient and unproductive economy. Since the restoration of democracy, with the first presidential elections in 1990, Poland has embraced the Western way: the conversion to the capitalist model has been neither blind and dogmatic, nor predatory. From the outset, Polish governments have followed a strategy aimed at preventing the forced sale of major public enterprises, avoiding uncontrolled corruption in the division of wealth and the consequent transformation of the state into an oligarchic system, as was the case in Russia, Belarus, many former Soviet republics of Central Asia and – at least for a first stretch – Ukraine.

This led to a slow process of privatisation and virtuous liberalisation, accompanied by the fertile use of European funds by successive governments. The result of these policies has been the creation of a strong productive fabric and an effective business network driven by innovation, with a strong and growing middle class. It has never been a minority of oligarchs (perhaps enriched in illicit ways before and during the collapse of communism, as was the case in Russia and elsewhere) who have held economic power in Poland, but rather a broader and more plural segment of the population, as is the case in more advanced economies. The result was the best-performing development model in Europe.

Poland’s accession to the European Union was the crucial lever for its extraordinary economic development, fostering a massive inflow of foreign capital and structural funds that fuelled growth and transformed the country into one of the most dynamic economies in Europe. Between 2016 and 2022, under a right-wing coalition government called Zjednoczona Prawica, Poland recorded an impressive 32% increase in GDP, compared to an EU average of 12%, making it the sixth largest economy in the Union. However, this growth took place in a context marked by strong international and domestic criticism for the right-wing government’s sovereignist and authoritarian tendencies, which undermined the solidity of the rule of law and the country’s credibility at European level. With the arrival of the new executive led by Donald Tusk, Poland is now committed to consolidating democratic foundations and fully restoring the rule of law, a process that has already led to the release of previously frozen EU funds. This new balance between economic growth and institutional reliability could further strengthen Poland’s position as a central player on the European stage, combining economic dynamism and political stability.

Illustrative image of Poland’s GDP per capita growth compared to the USA (source: World Bank)

Labour and unbureaucratisation as engines of development

Economic and political stability, together with a skilled and cheap workforce (at least in the first phase of the convergence process), made Poland a magnet for multinationals in sectors such as automotive, aeronautics, biotechnology and IT. Special Economic Zones, with their tax advantages (which other European regions, such as Italy’s Mezzogiorno, are now trying to imitate), have played a crucial role in this process. In addition, access to EU structural funds has enabled the country to improve its infrastructure, education and research, making it even more attractive to investors. Poland has also benefited from a significant inflow of human resources, especially from Ukraine, which has helped support economic growth. This foreign labour input has been so significant that it is estimated that without it, Poland’s GDP would have been about 10 per cent lower in recent years.

This mix of strategies has turned Poland into a hub for outsourcing and a thriving labour market, strengthening its position as one of the economic engines of Central Europe. Furthermore, the territory rich in mineral resources and inclined to agricultural cultivation make Poland one of the countries with the highest percentages of employment in the primary sector in the entire European Union.

The figure of the entrepreneur, whether Polish or foreign, is seen as the greatest creator of the nation’s growth and guarantor of employment and wealth redistribution. As proof of this, earnings and labour taxes on companies are the lowest in Europe, and the start-up time for a private company is, thanks also to measures such as the Reform of Company Law in Poland, 35% lower than the European average.

The Polish eagle guardian of European security

The United States has always seen Warsaw as its main ally in anti-Moscow (and at the same time Berlin’s containment) and, regardless of the transatlantic relationship, Warsaw is aware that it must first and foremost look after itself and its Baltic neighbours, with respect to the less and less theoretical risks of Russian aggression in the region. Geopolitical tension has intensified around the Suwalki Corridor, a strip of land about 65 km long connecting Poland to the Baltic States and separating Belarus from the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad. This corridor is seen as a critical point, NATO’s so-called ‘Achilles’ heel’, as Russian military action could isolate Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania from the rest of the alliance. Russia has shown strategic interest in the Baltic Sea, with joint military exercises with Belarus in this very area, raising concerns about a possible escalation. In response, Warsaw has not only strengthened its military presence on the border, but also planned a significant increase in defence spending, planning to spend 5% of its GDP by 2035 to ensure credible deterrence against any external threats.

This commitment comes in a context where Poland has already demonstrated robust economic growth, attracted foreign direct investment and benefited from EU funds to modernise its armed forces and defence infrastructure, preparing to protect not only itself but also its regional allies. Thanks to these defence investments, the inevitable process of defence integration in Europe will see Poland as a sure protagonist. Poland’s military capability, its strategic geographic location and its political will to play an active role in European security position it as a natural leader in any future common defence structure, advancing a security agenda that not only protects its borders but contributes to the overall stability of Europe.

The new engine of Europe

The strength to defend freedom, the tenacity and resilience that forged it and the determination to finally become a great power have led the Polish people to the most astonishing evolution in the years of the globalised world. Their strong sense of identity and simultaneous openness to the market are turning the rubble of communism into the new driving force of Europe.

Quoting entrepreneur and commentator Ole Lehmann, ‘the hard times of the 20th century created strong people. Now, strong people are creating good times’. And while most of the West is still struggling to get out of the 20th century pond, Poland has for all intents and purposes entered the 21st century and promises to drag the entire continent with it.