In Romania, European democracy is being defended against Putin’s mafia

The political crisis in Romania has raised crucial questions about the defence of democracy in the face of internal and external threats. The case of Călin Georgescu, an ultranationalist and pro-Russian candidate, is an emblematic example of how democratic institutions can react to such challenges.

In the presidential elections on 24 November 2024, Georgescu won a surprising majority in the first round, despite polls estimating him at 5%. This unexpected result turned the spotlight on possible outside interference, in particular from Russia. The Romanian authorities uncovered a massive disinformation campaign on social media, orchestrated by Moscow-backed influencers, with TikTok playing a central role. More than 25,000 accounts spread pro-candidate content, accompanied by suspicious funding and cyber attacks on the electoral infrastructure.

Faced with this evidence, the Constitutional Court of Romania unanimously annulled the first round of the elections, ordering a re-run of the vote. This was an unprecedented decision, motivated by the need to guarantee the legality and transparency of the electoral process, protecting national sovereignty from foreign interference. On 26 February 2025, Georgescu was arrested and interrogated by the General Prosecutor’s Office in Bucharest on charges of promoting a fascist organisation, spreading anti-Semitic propaganda and receiving illicit funding. Searches revealed large sums of money and direct links to Moscow among members of his entourage, further fuelling suspicions of a Russian attempt to destabilise Romania through the ballot box.

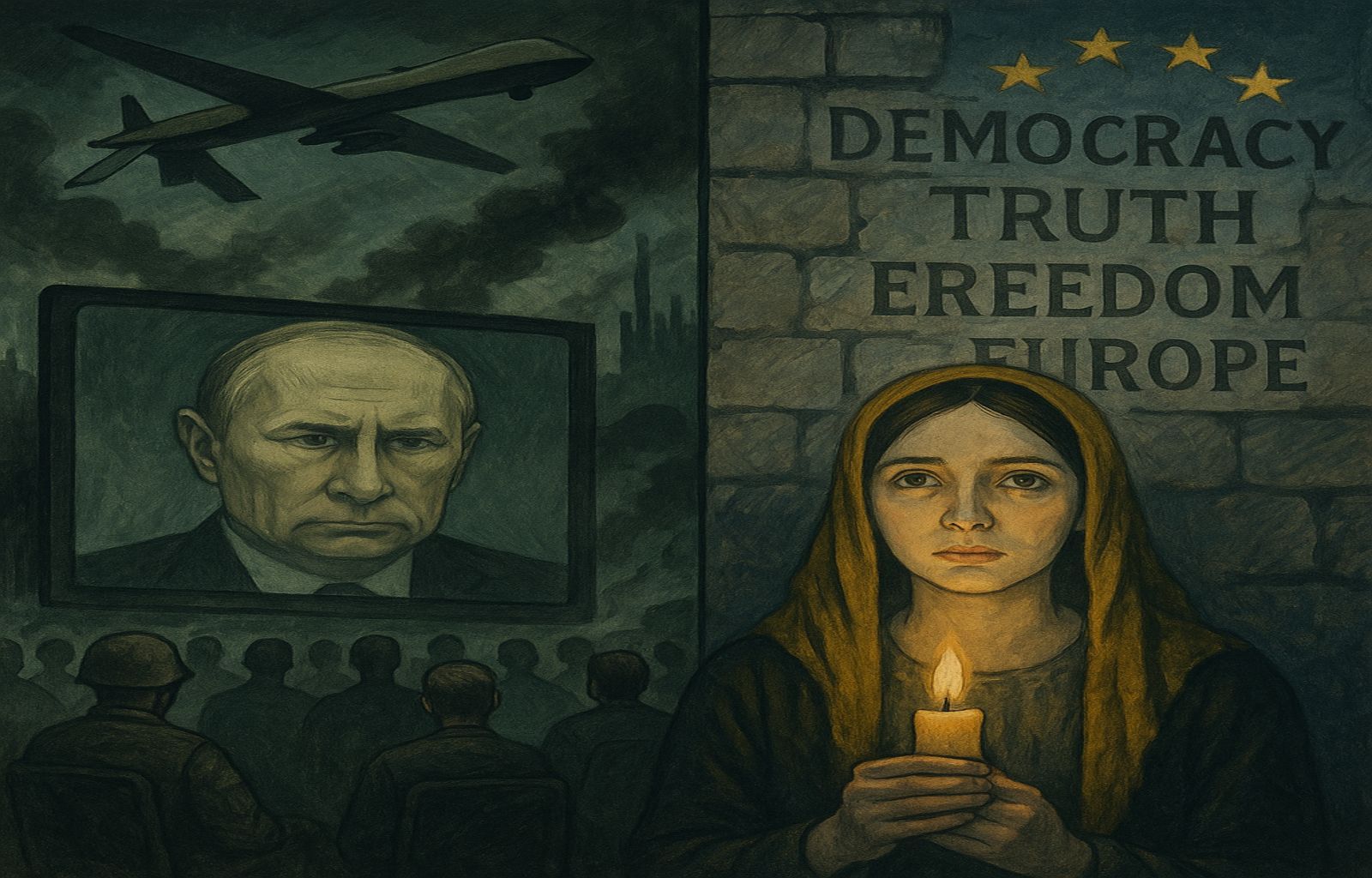

Europe under attack: Putin’s plan to hack democracy

The Romanian crisis is not an isolated case. From Romania to Italy, from Germany to France, Europe is under attack by Vladimir Putin’s regime, which is using the immense resources of Russia’s extractive economy to finance like-minded political movements and spread a widespread strategy of disinformation.

Putin fights not only with tanks and missiles, but with fake news, corruption and infiltration of democratic systems, supporting complacent leaders. His goal is not only to weaken Europe, but to install collaborationist governments, modelled on the Vichy regime in Nazi-occupied France, or if we want governments infiltrated by its mafia-like logic. It is no coincidence that in almost every European country there are parties and movements that faithfully repeat Kremlin propaganda, call for an end to support for Ukraine, and spread narratives designed to erode trust in liberal democracy.

This scenario raises fundamental questions: is it democratic to ban the candidature of an anti-Semitic extremist financed by a hostile power? Is it democratic to annul elections manipulated by outside interference? The answer lies in an essential principle: protecting democracy also means defending it from those who seek to destroy it from within.

Karl Popper, in his paradox of tolerance, stated that a genuinely tolerant society cannot afford to tolerate intolerance, on pain of its own self-destruction. If supremacist and anti-democratic movements are allowed to exploit democratic freedoms to gain access to power, they will use that same power to erase democracy. Popper did not call for the censorship of uncomfortable opinions, but emphasised the urgency of drawing a line when intolerant ideas threaten civil coexistence and fundamental rights.

Likewise, one cannot remain defenceless against those who attempt to hack democracy. A leader who foments ethnic hatred, receives funding from a hostile power and exploits freedom of expression to undermine the same freedom, represents an existential threat. In this context, banning his candidature and re-election is not an act of repression, but a mechanism of self-defence. Democracy is not just an electoral process: it is a system of values that must be protected.

The lesson for Europe

The Romanian case is a warning for the entire continent. Russia and other hostile actors are exploiting the fragilities of open societies to destabilise them from within. The strategy is no longer one of military invasion, but of ideological and cybernetic infiltration, aimed at undermining trust in institutions and fomenting divisions.

European leaders must learn from this episode and strengthen democratic protection mechanisms, without letting themselves be intimidated by accusations of ‘authoritarianism’ made by those who want to take advantage of their weakness.

Democracy is tolerance, but not suicide. Defending it means being ready to fight with the weapons of law, transparency and truth. Today more than ever, Europe’s fate depends on its ability to recognise and repel the threats that lurk within the meshes of its own pluralism.