Not only Greenland: the game for the Arctic has just begun

There is a new geopolitical fault line running through the world, and it passes through the Arctic ice. Once a remote and relatively peaceful region, it has now become the theatre of a growing dispute between superpowers, who are vying for control of natural resources, new trade routes, and strategic military positions. But the Arctic is not just a bilateral issue between Russia and the United States. It is a European issue. And if we do not deal with it decisively and with vision, we risk being cut off or, worse, used as pawns in a game that others are writing.

The Arctic heats up – literally and politically

Global warming is melting the ice at an unprecedented speed. According to the Copernicus Observatory, the European Arctic is the fastest warming area in the world. The retreat of the ice cap makes immense resources accessible: it is estimated that up to 25% of the world’s untapped reserves of conventional hydrocarbons are in the Arctic. Not only that: new maritime routes are opening up, such as the Northeast Passage along the Siberian coast, which drastically reduces shipping times between Asia and Europe.

But the consequences are not only economic: the shortest ballistic missile launch route between the US and Russia passes right over the Arctic. That is why the region is also a major military node.

Russia prepares, the West recoils

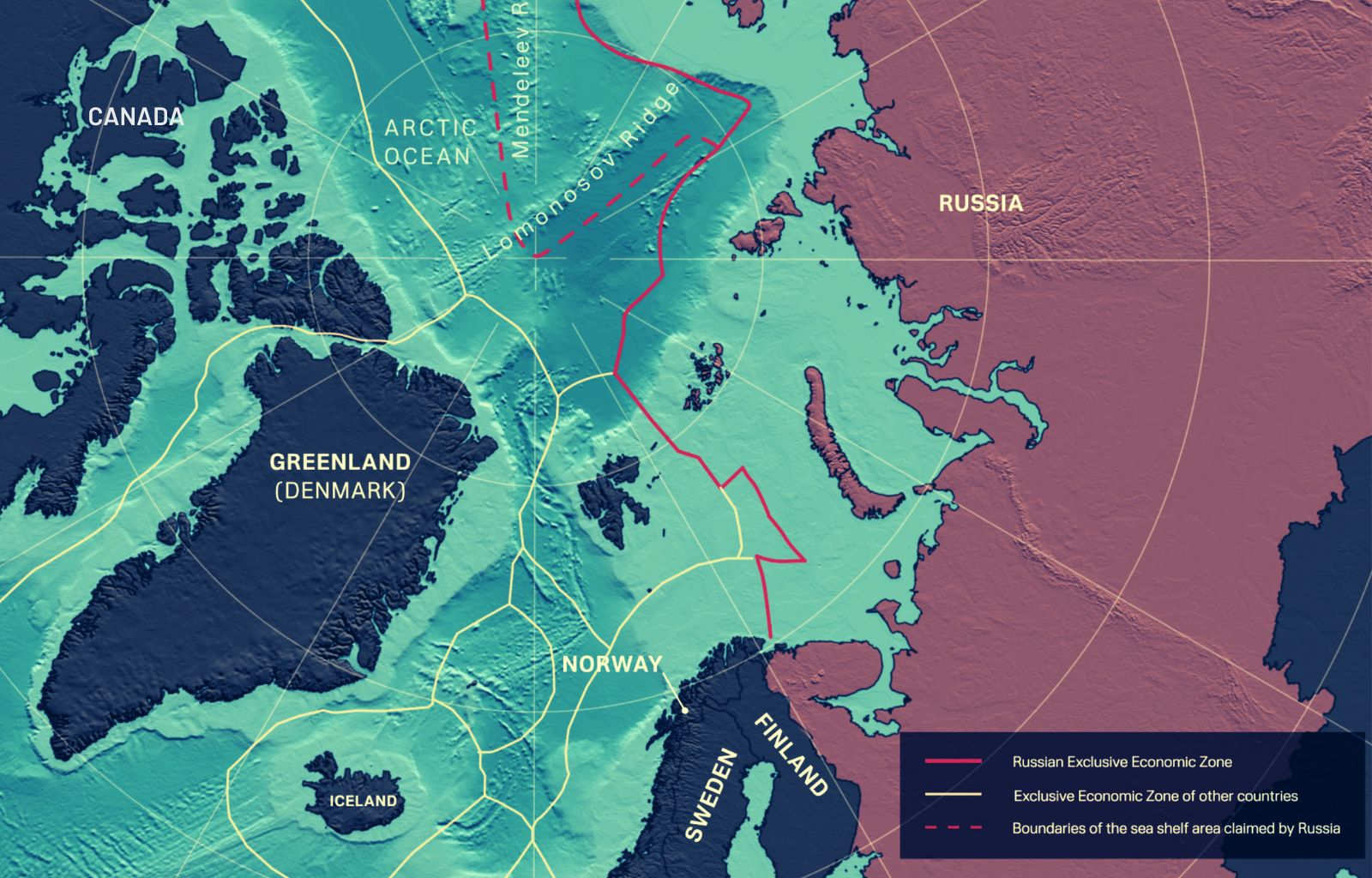

Vladimir Putin’s Russia has made the Arctic a strategic axis of its power projection. Since 2021, it has built 590 new military infrastructures in the region, reactivated Soviet bases, deployed advanced Su-34 and Su-35 fighters, installed radars, missiles and air defence systems. It has put to sea the world’s most powerful icebreaker fleet – 41 vessels, seven of which are nuclear-powered – and conducted Ocean-2024, the largest Arctic military exercise ever.

It has also violated the airspace of Scandinavian and North American countries, jammed NATO GPS signals, and cut submarine cables. Moscow already controls more than 50% of the Arctic coastline and draws more than 80% of its gas and 60% of its oil from this region. According to the US think tank CSIS, Russia’s militarisation of the Arctic is the most serious security threat to the US today.

The new American protagonism (and provocations)

It is therefore not surprising that the US, under the leadership of Donald Trump, has returned forcefully to the Arctic dossier. Trump has openly declared that he wants to ‘own’ Greenland, which is considered essential for national security and the US energy future. In February, Vice President JD Vance made a surprise visit to the US military base in Pituffik (formerly Thule), Greenland, declaring that ‘Denmark has so far been unable to secure the island’.

The Danish response came through the mouth of Foreign Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen, who recalled the 1951 bilateral agreement between Denmark, Greenland and the USA, which allows for an expansion of the American presence, provided it respects Danish sovereignty and within the framework of NATO (of which Greenland is a territory, thus covered by Article 5). He also issued a diplomatic provocation: in 1945, the US had 17 bases in Greenland; today, only one remains with about 200 men. ‘If the problem is the safety of the Arctic, let us solve it together‘. As if to say: if the goal is the partition of the world with Putin, then we are not in.

Greenland chooses Europe

Just as Vance landed on the island, a new national unity government took office in Nuuk, which excluded the more radical and pro-Trump party. The new Prime Minister, Jens-Frederik Nielsen, reiterated that Greenland’s independence from Copenhagen would be a gradual and responsible path, and rejected any possibility of an American ‘purchase’ or annexation, stating that the island’s future lay in cooperation with Europe.

The signal is clear: Greenland wants more self-determination, yes, but it does not intend to replace one protectorate with another.

Svalbard: a test case for Russian destabilisation

In the meantime, Russia is testing the limits of western tolerance on another Arctic front: Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago 1,000 km from Tromsø, governed by a 1920 treaty that assigns its sovereignty to Norway, but forbids any military use.

Moscow has stepped up provocations: sanctioned Russian officials arriving without permission, Victory Day parades, Soviet flags planted in abandoned villages. Now it accuses Oslo of ‘militarising’ the archipelago, an unfounded accusation that could serve as a pretext for escalation. As Elizabeth Braw of the Atlantic Council wrote on Politico.eu: ‘What happens on Svalbard, will not stay on Svalbard’.

Sweden prepares

Sweden, which has just joined NATO, is among the European countries most attentive to this development. It has reintroduced the military draft, strengthened its Arctic units, and – as the Wall Street Journal reported – considers Russia the main adversary in a possible conflict in the High North. Colonel Mattias Vainionpää confirmed that Sweden is preparing to be among the first to intervene in the event of an attack on Finland. Not surprisingly, 600 Swedish soldiers were recently deployed to Latvia for the country’s first NATO mission, strengthening the Alliance’s eastern flank. A strong signal.

What about China?

China observes and acts. It has no direct access to the Arctic, but has described itself as ‘quasi-Arctic‘ and has invested heavily in polar research and infrastructure. It is Russia’s main trading partner in the Arctic and a silent but growing player in the new global competition.

Ever since the Biden administration, the Pentagon has been sounding the alarm: the Sino-Russian link could create an antagonistic bloc capable of dominating the new Arctic routes and controlling strategic resources.

Europe must choose assertiveness

And Europe? The truth is that, until now, Europe has followed, reacted, but not led. Now is the time to do so.

We at L’Europeista propose a clear move: offer Greenland the creation of a European security mission, under Danish and French leadership, with the involvement of Sweden, Norway and the United Kingdom. A contingent that affirms with facts that Europe is there, and that if the issue is Arctic security, we are ready to do our part. But if the goal is a new partition of the world between Trump and Putin, then they will find firm, strategic and legitimate resistance in Europe.

The paralysis of multilateralism and the climate catastrophe

All of this is taking place against the backdrop of an unprecedented climate crisis: Arctic ice, melting at record speed, is not only freeing up resources and opening up routes, but also accelerating a global change that would require international – multilateral – cooperation that is now very difficult to achieve.

The Arctic Council – an intergovernmental body founded in 1996 – has seen its operational capacity progressively reduced following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Activities are now suspended or limited, and the multilateral dialogue between the eight Arctic states (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States) has been greatly reduced. In this context, there is a growing need to develop new instruments of regional cooperation, which would also include theCouncil’s permanent observers (Italy, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, India, Japan and China), while keeping the shared governance of routes and resources, respect for international law and the prevention of military crises at the centre. A chimera, unfortunately.