Georgia: Repression and Mass Layoffs Accompany New President

29 December 2024 was a day of deep political tensions and heated protests in Georgia’s capital Tbilisi, coinciding with the inauguration of former footballer Mikheil Kavelashvili as the new president. The ceremony, organised by the ruling Georgian Dream party, took place inside parliament and was attended by the oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili, founder of the party and a central and controversial figure in Georgian politics. However, the significant absence of the international diplomatic corps and the choice of not displaying European flags raised further doubts about the political orientation of the new leadership and its relationship with the country’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations. This absence of diplomatic representatives did not come as a surprise: Shalva Papuashvili, president of the parliament, had already anticipated that ambassadors would not be invited to the event, confirming a sign of growing international isolation.

Mass redundancies in Georgia heading towards 2025

In the run-up to New Year’s Eve, Georgia witnessed an unprecedented mass dismissal of numerous civil servants. According to political observers, the dismissals are aimed at eliminating officials deemed critical of the government line, particularly those who support Georgia’s Europeanist aspirations.

Repressive laws to stop protests

At the same time as Kavelashvili took office, a set of repressive laws, hastily passed by the parliament controlled by the Georgian Dream party, was signed by the new president immediately after he was sworn in and published in the official gazette on Sunday evening, making them effective as of Monday. These regulations immediately raised criticism, as they appear to be aimed at restricting the right to protest and civil liberties, specifically targeting activities commonly used in street demonstrations.

New repressive measures

Prohibitions during events:

- Use of fireworks and lasers: fine of 2,000 lari.

- Covering the face with masks or other means: fine of 2,000 lari.

Traffic restrictions:

- Organised blocking of roads or group movements impeding traffic: fine of 1,000 lari and suspension of driving licence for one year.

Unauthorised visual protest:

- Placing stencils, writing or posters that spoil the aesthetics of the city: a fine of 1,000 lari (previously 50 lari). In the event of a repeat offence, the fine rises to 2,000 or 3,000 lari.

Abuse of uniforms:

- Illegally wearing uniforms or symbols similar to those of the Ministry of the Interior: fine of 2,000 lari.

Harsher penalties for roadblocks:

- Participation in roadblocks: fine increased from 500 to 5000 lari.

- Organisation of such blockades: fine increased from 5,000 to 15,000 lari.

The measures, effective as of 30 December, are perceived as a clear attempt to stifle public dissent. Prohibited activities, such as the use of masks, fireworks and roadblocks, are in fact frequently used in demonstrations, and the laws introduced aim to significantly limit the population’s ability to express dissent.

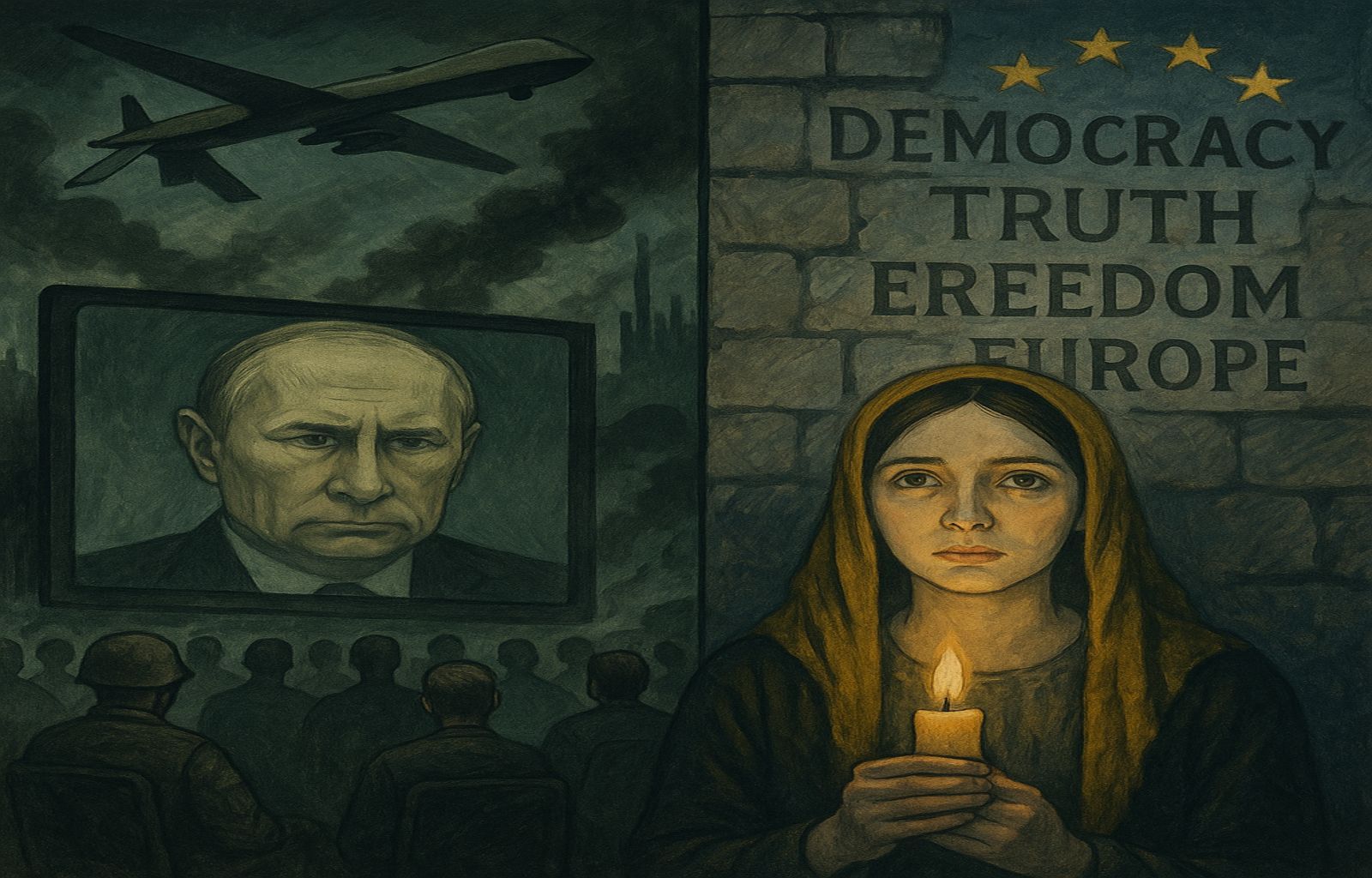

Mass protests in Tbilisi

Despite everything, every day thousands of pro-EU protesters continue to take to the streets in the capital Tbilisi and in the rest of the country for more than a month now, led by the now former president of Georgia, Salome Zourabichvili, who, after initially refusing to relinquish power, resigned declaring that she will continue to ‘protest alongside the people, fighting for new elections’, reiterating that she ‘does not recognise the legitimacy’ of the new president, Mikheil Kavelashvili, calling the elections ‘a farce’.

In a public speech, former President Zourabichvili then announced that he would take part in a large protest scheduled for 31 December, after accusing Kavelashvili of having ‘betrayed’ Georgian western aspirations, calling him ‘illegitimate’ and calling for a new commitment to Georgia’s integration into the Euro-Atlantic sphere.

A glimpse into the future

Internal political tensions, pro-EU demonstrations, mass layoffs and new repressive laws seem to map out an increasingly dark future for Georgia. Kavelashvili’s inauguration, accompanied by authoritarian decisions and increasing international isolation, marks a turning point that could deepen divisions in the country. With control firmly in the hands of a leadership perceived as repressive and distant from the pro-European aspirations of a significant part of the population, the risk is that of a further deterioration of civil and democratic rights.

Nevertheless, Georgian civil society continues to demonstrate in all its components, united in demanding a future in the European Union and the Atlantic alliance. The citizens’ determination not to give up these aspirations is a sign of hope, but at the same time an urgent appeal to the European Union not to betray them. Now more than ever, international support is crucial to prevent Georgia from sinking further into authoritarianism and to support those fighting for a democratic and free future.