Silences and apparent defeats: where to look for Francis’ legacy

In the aftermath of the death of Pope Francis, there is a strong temptation to pass judgement on his work by doing a sort of cubist painting: that is, putting everything he did or said on the same level, and then selecting what we liked more or less according to our conservative or progressive sympathies.

‘Conservative’ or ‘progressive’, we mean, according to the parameters of the secularised West in which we live.

As for me, I preferred to do something different and examine the issue starting from a personal conviction of mine, which Francis probably also had: the conviction that humanity today has a very strong need for the Gospel and a growing thirst for an encounter with the Christian faith.

Already in the 1960s the Second Vatican Council recognised that ‘the joys and hopes, the sorrows and anxieties of people today are also those of Christ’s disciples’.

But now this feeling is even more widespread, and, from time to time, supported by data.

In Western societies, Generation Z, perhaps exhausted by the “social scourge of loneliness”, the “culture of indifference” and the “materialism that anaesthetises us”, is showing the first timid signs of a resurgence of religiosity.

There is conflicting data on China, but there are those who think that an easing of repression could make it the country with the most Christians in the world in a few years.

As for developing societies, they are divided between those that have already been Christian for generations, those where several cults coexist in a precarious balance (with Christians often the victims of ferocious offensives) and those where conversions are forbidden but something is moving underground (in Iran there is talk of hundreds of thousands, if not already millions, of undeclared Christians).

The lion’s share is taken by the evangelical Protestant churches, smaller, nimble and attractive with their enthusiasm that at times borders on sectarianism. But the slow-moving Catholic pachyderm is more able to stand the test of time.

Moreover, it is the only one that, with its hierarchy and media reach, is able to speak ‘in the name of Christianity’ on world television, offering a more or less coherent image of it to the Buddhist worker in Vietnam as to the Muslim clerk in Indonesia.

It is clear that not everyone shares my confidence in the Christian message as medicine for the ills of today. For many this will sound tedious or even harassing.

But a judgement on Pope Francis must be made within this framework and with this order of priorities, for the simple fact that this was the framework in which Francis moved and this was the order of priorities he had. ‘Reality comes before the idea and time comes before space’.

The mother of all reforms

And it is precisely in the light of these considerations, and not of Western progressive ideology, that the greatest novelty brought by Francis should be viewed: the opening of the debate on the return of the female diaconate.

A debate that, let us remember, has so far come to nothing. A ‘failure’ according to the criteria with which we define ‘success’ today, and a ‘defeat’ in the face of what we are used to calling a ‘victory’.

But the Church has different criteria. When it moves, it must consistently carry with it two millennia of history, one fifth of humanity and 73 books of Holy Scripture.

No wonder its steps are always cautious and gradual: that of the ‘monarch pope’ who with a wave of a magic wand can turn everything upside down at his whim is a macchiatrical caricature that has never been borne out in facts.

Now, for centuries women were only part of the regular clergy (nuns and sisters). Sure, sometimes in that capacity they made and unmade empires and changed the course of history, but in the daily lives of the faithful the clerics of reference (bishops, priests and deacons) have been, at least since the late Middle Ages, only male. In communities, moreover, where often the most assiduous, most industrious, most devout and most esteemed people were precisely women.

The Church, therefore, has immense untapped potential: access to the diaconate would allow women, even married women and mothers, to preach, to celebrate marriages and baptisms, and above all to have a say alongside priests in the concrete management of communities.

It would be a revolution in the way the Church is lived and perceived. Those who, like me, want their children to follow a Christian path, can clearly imagine the difference. For others, perhaps a little more imagination is needed, but it is not impossible.

Needless to emphasise the beneficial effect this power-sharing with female ministers would have on scourges such as paedophilia in developed countries and concubinage in African countries.

Of course, if in the former ‘third world’ there are those who oppose this turnaround out of a patriarchal mentality, in the former ‘first world’ there are those who consider it insufficient and even call for equal access of women to the priesthood or a prominent role of ordinary believers (the ‘laity’) in the management of communities, according to a more or less democratic spirit.

In such a Mexican-style stalemate, it is not surprising that Francis’ twelve years were not enough to make progress. But for the first time in at least a millennium, the dossier is on the table.

If someone had told my great-grandmother, she would not have believed it.

A wise view of the environment

Then there is a second challenge that Francis has given us the tools to tackle, even though it is far from being won: that of climate change and the degradation of natural environments.

His Laudato si’ has been the most popular environmental text in the world for a decade.

Its secret? Not being an environmentalist text, as we imagine it to be in the West since the days of Al Gore and Naomi Klein, but a religious encyclical, which sees environmental degradation as the visible imprint of a spiritual degradation.

The ‘culture of waste’ wounds humans much earlier and more painfully than it wounds animals and plants, and the ‘care of the common home’ has as its first purpose to restore full dignity to God’s most worthy creature.

Francis’ ‘integral ecology’, in short, is a triumph of humanism, and in this it contrasts with both dominant currents of Western environmentalism: on the one hand the paganising pantheism, animated by a creeping contempt for man and a senile weariness towards civilisation, which is the essence of radical left-wing environmentalism; on the other hand, the blind veneration of research and technology, considered sufficient to engineeringly reorganise the ecosystem, with selfish calculation over the long term as the only motive, which prevails in the environmentalism of the moderate right.

All of this having disproved from the very first chapter, with incontrovertible data, anyone from the extreme right who denies the climate problem at all.

Put in these terms, the fight for the environment becomes digestible even for developing countries, which are by no means tired of civilisation, but neither do they have the luxury of being able to make selfish long-term calculations.

Laudato si’, we could say, has created an environmentalism tailored to that immense part of the world for which dogs are not children (to cite another famous slapstick of the pope’s that caused a scandal in the well-thinking West).

And the fruits of this gamble, perhaps, will also soon be reaped.

The controversial political choices

Ordinary believers care little or nothing what the bishop of Rome thinks about contemporary political crises. The pope is as infallible in matters of faith and insofar as he respects the Councils as a mathematician is infallible in matters of mathematics and insofar as he respects the axioms. On everything else, his is an opinion that one may or may not share.

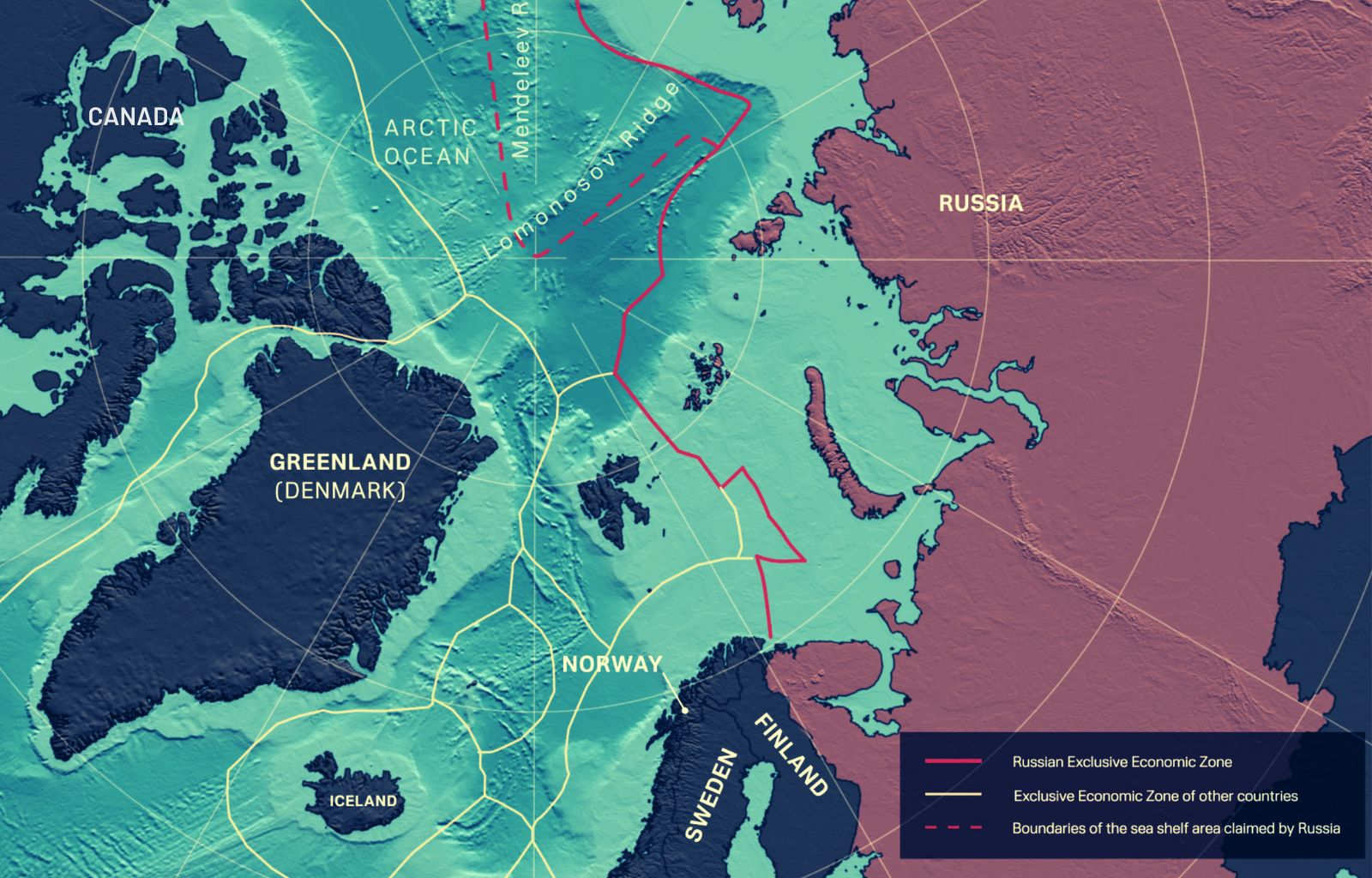

Certainly, the Ukrainians felt betrayed by Francis’ stubborn neutrality on a conflict in which they were unquestionably the aggressors, and, worse still, by his occasional encroachments on their murderer’s rhetoric (“NATO barking at Russia’s doorstep“, “The courage to raise the white flag” etc.).

But this, and I say this as a proud supporter ofUkraine, is because the Church understood earlier and better than others what was really at stake in the conflict.

When our media were still babbling about Crimea, ‘Russian-speakers in the Donbass’, ‘NATO expansion’ and other red herrings, the Church already knew full well that this was the decisive war for the survival or destruction of the liberal world order.

The order, that is, that was born out of the dissolution of European empires according to European values (national independence, preference for democratic government, free trade) starting with the Spanish empire in the Americas and ending with the Russian empire in recent years.

Now, Francis may have had a few anti-Western rants coming from Argentina’s Peronist rhetoric, but his successors will not change their minds about this neutrality.

For it was the liberal West that turned its back on Christianity, not vice versa. Precisely in the bright decades following the Second Vatican Council, when it seemed that the liberal world order and the Christian faith could coexist in peace, there was mass desertion from Christianity in the countries that supported that order.

How can we, Western liberals, claim to have our wife drunk and our barrels full?

Why should the Church expose itself in such a dangerous war crisis (moreover, with irrelevant concrete effects) in defence of an order built by people who now ignore or even attack it?

The same applies to the dialogue with the authorities of Islam, which at times has had ugly lapses in style (baby Jesus wearing a keffiyeh…) and has always turned the noses up at the champions of human rights. Not to mention the agreement with the Chinese authorities.

But even here: what was the alternative?

The Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and China are countries where converts to Christianity are more or less brutally persecuted, and where at the moment the survival and expansion of the Church depends only on the approval of those authorities.

Moreover, with rare exceptions, these are countries where the West has been unable (or unwilling) to export any fundamental freedoms, starting with freedom of worship or freedom of marriage for women, despite long decades of relations.

Do we really expect the pope to do, worse and in vain, what Bush, Obama and Biden failed to do?

Come on, let’s be serious.

Francis’ silent gift to the West

One gift, however, Francis has given to our liberal order. A great gift.

And it is not something he chose to do, but something he very prudently chose not to do.

In the twelve years that have seen the overwhelming and coordinated rise of authoritarian, fanatical and sometimes openly racist political parties across the West, Francis has never, never for a minute lent the Catholic Church to their rhetoric.

No alliance between Tiktok and altar has paved the way for a new Restoration.

He deserves credit for that. And, in the face of this, I believe it is our duty to swallow all the bitter morsels of ‘barking NATO’, ‘too much faggotry’, ‘killer doctors’ and dogs that are not children.

Thank you, Your Holiness.