The ‘democratisation’ in America: Tocqueville’s prophecy come true?

Quoting Alexis de Tocqueville and Democracy in America is very fashionable in recent years, marked as they are by a surge of despotic and totalitarian instincts in our societies.

For those who do not know this polite French philosopher from the mid-19th century, let us summarise the main events of his life. An aristocrat from a lineage linked to the Bourbons until 1830, he resented the parliamentary monarchy of the Orléans and went on a diplomatic mission to the United States. There he became convinced that the spread of equality and democracy was now the inevitable destiny of all mankind. He advised moderate liberals like himself to accept this fait accompli and to take steps to prevent new threats to human freedom from arising from the same equality and democracy. This is precisely what Democracy in America was about, which came out in two volumes between 1835 and 1840 and immediately became a bestseller.

Consistent with his ideas, Tocqueville took part in the 1848 revolution, was a deputy and then a minister in the Second Republic, tried in vain to hinder Louis Bonaparte’s rise to power and was marginalised from political life during the Second Empire.

‘Neat, sweet and pleasant servants’

France, and the world, was left with his philosophical masterpiece. This concluded with the foreboding that a ‘new species of oppression, resembling none of those that existed in the past’ might arrive , with ‘a single, omnipotent power, similar to a guardian, but elected by the citizens’ that would impose ‘an orderly, sweet and pleasant servitude, more compatible than imagined with many external forms of freedom’.

Recently, after observing the exploits of Orbán, Lukashenko, Erdogan, Vucić, Ivanishvili and other autocrats of the digital age, journalists have invented a term that, however ugly, fits well with what Tocqueville had in mind: ‘democratisation’.

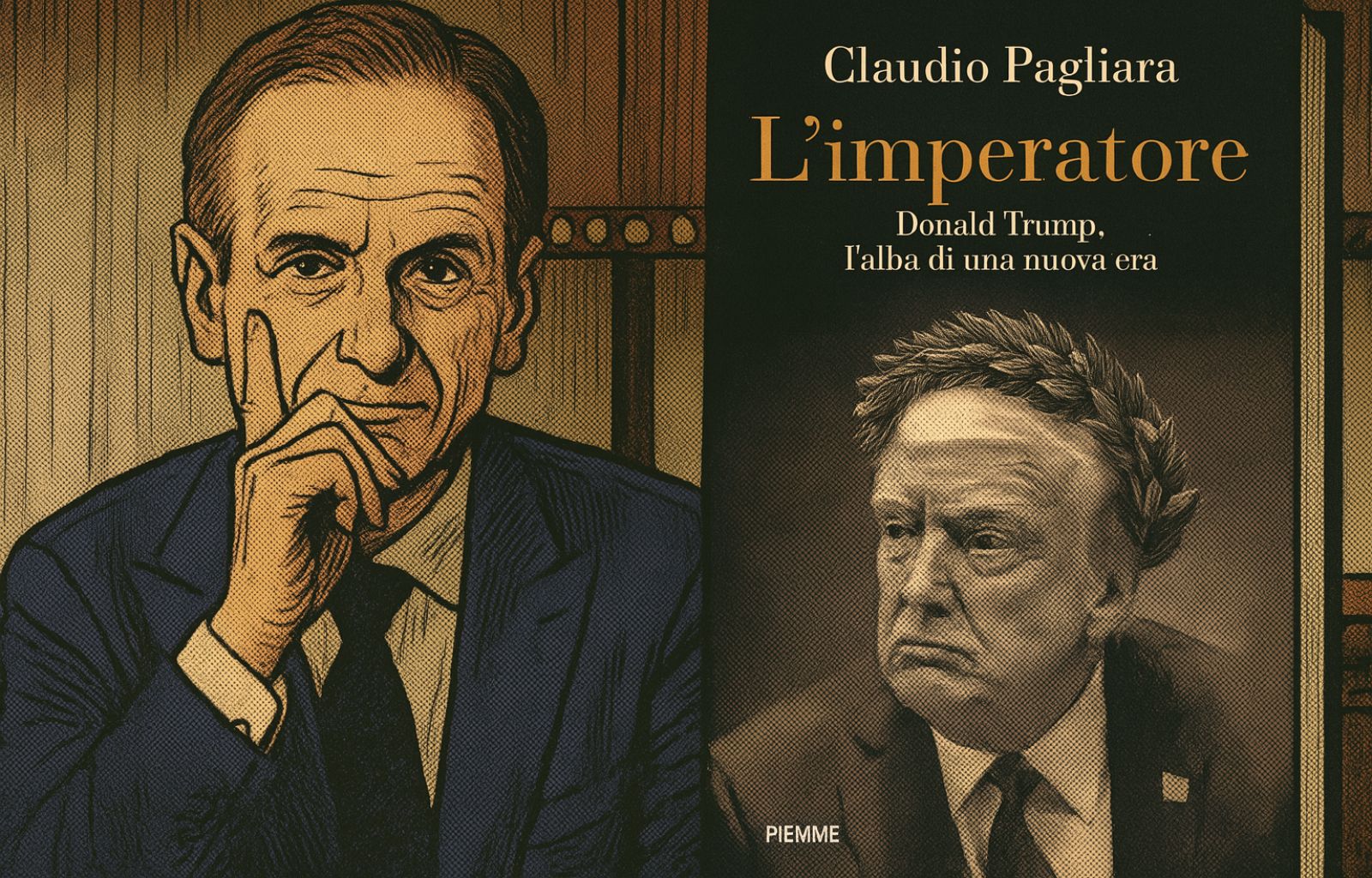

And Tocqueville’s has become a classic self-fulfilling prophecy. All the more so at a time when Donald Trump himself, who is not just any Balkan dictator but the President of the United States, is launching a systematic attack against some of the counterweights that, according to Tocqueville, allowed democracy not to degenerate into a new tyranny: the independence of judges, the independence of the press, the obligation to delegate certain acts of government to officials not chosen by the President* and, above all, respect for forms.

Equally strong is the temptation to trace in today’s America a breakdown of the cultural pillars that, according to the philosopher, supported democracy in America at the time, such as religious devotion and the study of the classics.

But these reflections only make sense if Tocqueville’s thinking can help us explain how we got here. If the old aristocrat had only ‘guessed by shooting at random’, in fact, the search for correspondences between his oracles of 1840 and the reality of 2025 would be reduced to a tombola with no concrete effects.

Let us look, then, for the architrave of Tocqueville’s thought. In all likelihood, it is his reading of history under the banner of continuity rather than discontinuity. In his eyes, revolutionary ruptures do not exist, or, at any rate, are only apparent. The mentality that gave birth to democracy had already developed under absolutism, and the mentality that will give birth to the ‘new oppression’ is already developing under democracy. The real danger to democratic societies, in short, is not the reaction of nostalgics who regret a tyranny similar to those of the past: it is a set of habits and feelings that are the fruit of democratic society itself.

Democratic societies, to take just one example, do not find the centralisation of power in the hands of a single ruler (i.e. the president and his government) scandalous. This is due on the one hand to the fact that the sovereign is chosen by the people, and on the other hand to the disappearance of a noble class animated by passions such as honour, glory and jealousy of their privileges, which historically was the most reluctant to cede shares of power.

A system in which the sovereign receives his electoral mandate from the citizens and then exercises it without any restraint appears, therefore, as a good compromise between the habit of freedom and the habit of centralisation of power, both typical of democracies. If we are to listen to Tocqueville, in short, Trump’s tweet: ‘He who defends his country violates no law!’ meets with far more approval in a democracy than it would in a feudal society or one with restricted suffrage.

Of course, Tocqueville realised that such a system would soon turn the moment of voting into a pure formality with no real competition. If the president-sovereign can act without external constraints, he only needs one term of office to guarantee himself absolute power and turn every subsequent election into a coronation. Louis Bonaparte, to the philosopher’s great sorrow, did exactly that.

But Tocqueville also warned against the elitist temptation to reconstruct a ‘new nobility’, no longer of blood but of spirit, to act as a sentinel against the ambitions of presidents within democracy. Decades of habituation to political equality make ordinary people allergic to the idea that one social class (of whatever kind) can once again exercise a prominent public role over the others. Today, we realise with ease that proposals such as the ‘licence to vote’ or the rhetoric of ‘this ignorant person’s vote is as good as mine’ sound not only hateful, but also out of touch with reality. The Kamala Harris campaign has paid dearly for this kind of bluster.

The only major exceptions for Tocqueville were judges and civil servants, but in America then as now, they were largely elective and subject to rotation: nothing like a self-referential, untouchable caste. Making these countervailing figures look like parasitic castes, indeed, is precisely the crux of the clumsy propaganda effort with which Elon Musk is accompanying the mass purges of his DOGE(Department Of Government Efficiency).

Certainly, the centralisation of power in the US has its strongest counterweight in the existence of the 50 individual states alongside the federal bodies. And this counterweight is the only one that does not seem to be collapsing, and perhaps cannot collapse, under the blows of the Trumpian offensive. Moreover, it is the only forum in which the Democratic Party can currently mount a modicum of resistance.

Let’s be clear: even a section of the American left has recently attacked certain cornerstones of democracy such as freedom of the press, freedom of teaching, freedom of research or selection on merit. It has imposed on entire universities and even entire school districts a denigrating reinterpretation of American history as ‘genocidal’, ‘supremacist’ or ‘patriarchal’ (moreover, while becoming infatuated with a genocidal, supremacist and patriarchal machine as real as Hamas in the Gaza Strip). The dual desire ‘to be led and to feel free’, from which for Tocqueville the new despotism would spring, is reflected in the affirmative actions of the left no less than in the charismatic mysticism of the right.

‘The final clash for American democracy: two irreconcilable visions of equality’

The fact remains, however, that there has been no large-scale attempt on Joe Biden’s part to replace state departments with courts loyal to him, to discredit the judiciary, to trample all forms to the point of denying the existence of election results unfavourable to him, and thus to lay the groundwork for turning the next election into mere coronations. The woke wing of the Democrats has repeatedly scratched the rule of law, but the MAGA wing of the Republicans is directly trying to kill it. In this final clash between Trump’s followers and the constellation of counterweights accumulated over centuries of US democracy, we do not know who will win. We do know, however, thanks to Tocqueville, that it is a clash that has been foreseen since time immemorial, and that it is not a clash between democracy and its enemies, but a clash between two different visions of democracy: one that sees in the omnipotence of the elected an advantage for the voter, the other that sees in the omnipotence of the sovereign a danger for the citizen. Two different ways of reconciling equality and freedom, one of which ultimately destroys them both, while the other, with a thousand limitations, saves them.