The future of the planet passes through Greenland: Trump gets it, Europe still doesn’t

‘For the United States, buying Greenland is a necessity‘. Donald Trump declared this a few days ago, and the pattern is the usual: he throws a huge rock into the pond, the noise surprises everyone, the more distracted snub his words, the opponents ridicule them. This is a mistake: even when he uses bizarre and provocative tones, Trump knows exactly what he is saying. In the case of Greenland, this is not the first time Trump has evoked interest in acquisition (but we should more appropriately speak of annexation): he had already done so in 2019. Even at the time, the idea aroused scepticism and irony, and the matter seemed to be closed with the very clear statements of the Danish Prime Minister, Mette Frederiksen: ‘Greenland is not for sale‘ (Greenland, for those who do not know, is an autonomous territory belonging to the Kingdom of Denmark, as are the Faroe Islands).

Yet, to signal the seriousness of the proposal, after Frederiksen’s sharp closure, Trump cancelled an already scheduled visit to Denmark, causing embarrassment in Copenhagen (video).

More than a provocation: this is why Trump is serious

In 2020, General Covid overwhelmed Trump and his re-election hopes, effectively freezing the Greenland issue, which The Donald is now, however, reproposing in all its rawness. Be careful: in the context of the growing global competition over the Arctic, his words take on a profound strategic significance that should not be underestimated. Greenland, the largest island on the planet, is not just a remote block of ice, but a crucial node of natural resources, trade routes and geopolitical interests.

Wanting to speak in the plain language of the average American, and having basically no other language than that, Trump presents the matter almost as a real estate deal. It is obviously unlikely, indeed impossible, that the deal will be concluded in front of a notary and in the presence of a real estate agent. Yet it is important to point out that Trump does not use abstruse categories, but explicit historical references: one, in 1867, Secretary of State William Seward negotiated the purchase of Alaskan territory from Russia for $7.2 million, a deal that was dubbed Seward’s folly at the time by critics, who were convinced it was a waste of money on a remote and inhospitable land (in time, it turned out to be a brilliant strategic move); two, in 1946, US President Harry Truman proposed the purchase of Greenland from Denmark for 100 million dollars; Denmark rejected the offer, but American interest nevertheless led to the construction of the Thule military base in the north of the island. Moreover, it is important to place Trump’s offer in the turbulent political context of the small Greenlandic community, animated by increasingly strong separatist drives from the Danish colonial ‘power’.

A strategic land at the centre of climate change

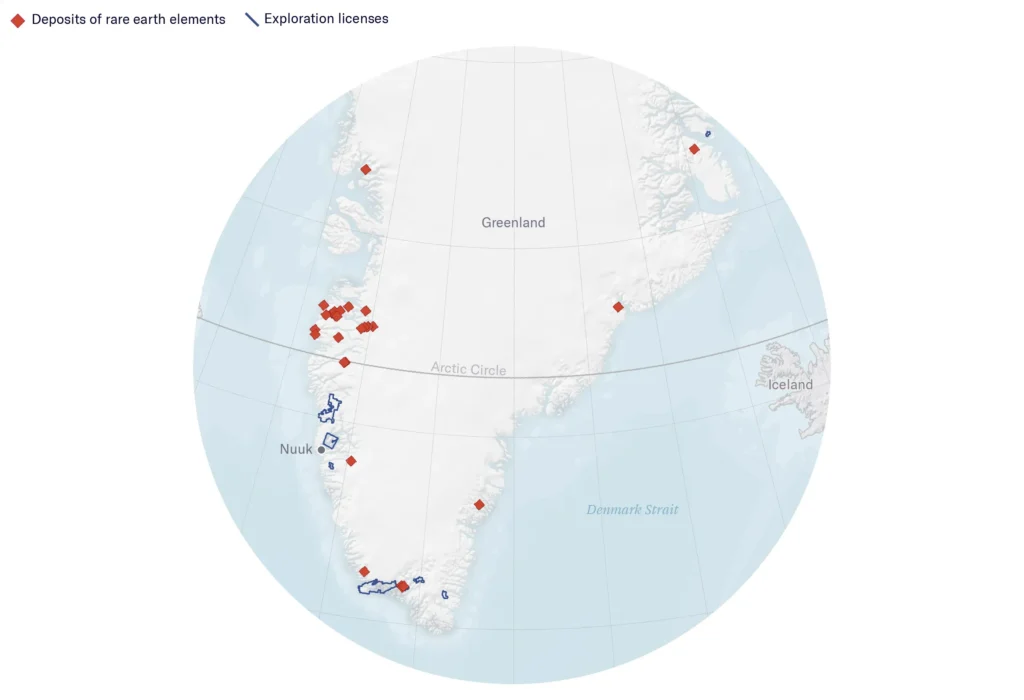

With a surface area three times that of France and a territory 80 per cent covered by ice, Greenland is emerging as a nerve centre of the global chessboard. Climate change, which melts some 200 billion tonnes of ice each year, is revealing and making the island’s immense natural resources increasingly accessible. These include hydrocarbons, including oil and natural gas, but especially significant reserves of rare earths, indispensable for advanced technology and defence systems. In addition, melting ice is opening up new shipping routes, such as the North Sea Route, which connects Europe and Asia and drastically reduces shipping time. Greenland thus finds itself at the centre of a global geopolitical game, in which major powers vie for control and influence.

The United States and Arctic ambition

The United States sees Greenland as a crucial bulwark for national security and the indispensable outpost for future control of the Arctic. The first Trump Administration announced in late 2019 the reopening of the consulate general in Nuuk (closed since 1953), which then materially took place in June 2020 (thus, without any second thoughts from the Biden Administration). Parallel to the expansion of diplomacy, the US has significantly increased its military presence in the region. Among the most visible initiatives is the dispatch of four latest-generation F-35 fighter jets to the Thule base. The base represents the northernmost point of US military installations in the world and has been modernised in recent years to meet new strategic requirements. Finally, the new US ambassador in Copenhagen, already appointed by Trump. Who is it? Ken Howery, US entrepreneur and investor, known for being one of the co-founders of PayPal along with Elon Musk, among others. After the sale of PayPal to eBay in 2002, Howery continued his career in the venture capital industry, founding in 2005, together with Thiel and Nosek, Founders Fund, a venture capital firm that today manages over $3 billion in investments. Howery has already held diplomatic posts: from 2019 to 2021, under Trump, he served as US ambassador to Sweden. In short, we are talking about an old acquaintance of both the newly elected president and his main sponsor, who was not slow to ‘assign’ Howery to help Trump in the Greenland purchase deal.

China and economic strategy

It is not just Washington’s eyes on Greenland. On the contrary, from many points of view, it is good that Donald Trump has placed so much attention on the Arctic island, because a few years ago, someone else’s sights were already set on Greenland: China. Beijing had opened a dialogue with the Nuuk government similar to the one it has with some African governments, to which it offers generous financing and credit lines for the construction of infrastructure, in exchange for full entry into the economy of the country in question and licences to exploit its natural resources. The first significant affair concerns airports. In 2017, the Nuuk government was looking for funds to build new airports, crucial infrastructure to improve mobility and promote the island’s economic development. Beijing offered to finance the project, on the condition that the construction would be entrusted to Chinese companies. The initiative provoked an immediate western reaction: Washington began strong pressure on Denmark, which eventually intervened with direct funding to prevent Chinese access. But it is on rare earths that the greatest Chinese pressure is being felt on the island: Shenghe Resources (controlled by the Chinese government) holds the controlling stake in Energy Transition Minerals (formerly Greenland Minerals), an Australian listed company that owns the Kvanefjeld area, which according to major surveys could be the second largest site in the world for availability of rare earth oxides and the sixth largest in the world for availability of uranium. So far, thanks mainly to pressure from the United States and to a lesser extent the European Union, uranium mining is banned, but as the turmoil during the Greenlandic general election in 2021 has already shown, the exploitation of the enormous resources is and remains an open question for a small community that is currently only extremely dependent on fishing and subsidies from the Danish government.

Russia and Arctic Expansion

Russia also plays a role in the Greenlandic game, although less directly than the US and China. Moscow has expanded its military presence in the Arctic, developing infrastructure along the North Sea Route and strengthening its Arctic fleet. Although Russia has no direct territorial claims on Greenland (it does have claims on Svalbard, to which we will devote a future article), the growing American and Chinese focus on the island poses a challenge for Moscow. Some Russian officials have speculated that direct US control over the island could turn it into a strategic military base within walking distance of the Russian borders, fuelling tensions in the region. Moreover, Russian rhetoric has sought to equate US ambitions on Greenland with its own actions in Ukraine. Elena Panina, a United Russia MP, stated that Trump’s proposal to buy Greenland is a clear example of US imperialism, adding that this basically justifies Russia’s actions in Ukraine’s ‘own geopolitical backyard’.

Europe: a strategy yet to be defined

What about Europe? In this context of increasing competition, Europe risks remaining a spectator. Or rather, a paying spectator. Although Greenland is formally part of the Kingdom of Denmark, it is not part of the European Union, by virtue of a 1985 referendum in which the island’s population decided to leave the EEC, essentially so as not to have to follow continental regulation on fishing, but has chosen for itself the status of an overseas territory.

Greenland therefore receives funding from the EU for sustainable development and has signed agreements that strengthen cooperation with Brussels, as well as obviously having Denmark (and the rest of the Old Continent) as the main outlet for its products. The associated relationship with the Union also means that all citizens of the Kingdom of Denmark residing in Greenland (Greenlandic citizens) are European citizens and therefore free to move and reside freely throughout the entire EU territory. Furthermore, the only exemption that the EU recognises from the ban on the sale of seal hunting products concerns Greenland’s Inuit community.

In short, Europe supports the Greenlandic population with its instruments, just as Denmark does with even more fiscal resources, but today appears to be totally absent from the great game that is developing around the island and lacks an action plan that would allow it to keep Greenland in its strategic orbit.

Europe does not only offer subsidies, but real investment

How can Europe move more decisively? First of all, an ambitious strategy is needed. Brussels must offer major investments, both infrastructural and social, demonstrating to Greenlanders that Europe can be the most reliable, beneficial and respectful partner for autonomy and sovereignty, even in the great and inevitable game of mineral resource exploitation . This could include the financing of sustainable development projects, the construction of modern infrastructure and economic support to improve the quality of life and work on the island. Furthermore, the EU should intensify scientific and environmental cooperation in the Arctic, developing innovative solutions to address the challenges posed by climate change. Last but not least, there is a need for Europe (and its major countries, as long as there is no single defence) to invest militarily in the presence and protection of the island, its resources and the routes through it. Denmark has already – just after Trump’s recent statements – announced an initial investment package in the island’s security of around €1.5 billion. This is pocket change, of course, but it is unthinkable that more significant investments would be made by Denmark alone.

Greenland is not just a question of resources or trade routes: it is a question of the future, strategy and global role. The United States, China and Russia have understood this and are already acting to consolidate their influence. Europe, on the other hand, has yet to prove that it is up to the challenge. To prevent it from slipping out of its sphere of influence, Brussels must act with vision and determination. By offering infrastructural, social and strategic investments, Europe can keep Greenland bound to itself, consolidating its role as a player in the Arctic. The time to act is now, the Greenlanders will not wait forever, nor will the marauding great powers.