Three years, three wars. A review of Ukraine on the eve of Trump’s return

In less than a week Donald Trump will take office again as president of the United States. To understand the options he faces on Ukraine, it is useful to take stock of how the conflict has gone so far, during Joe Biden‘s years in office.

As the data show long-term trends, in fact, it becomes easier to understand whether and how the bloody course of the war has been influenced by the choices of the former White House tenant, how far his successor should deviate from his strategy, and in which direction he should do so.

A war on three levels

Let us begin with a brief summary of the facts. First of all, it is important to clarify that Vladimir Putin ‘s regime has waged war on three levels:

- the war on the ground against the Ukrainians;

- the economic war against the Ukrainians (to which their allies responded by waging one against the Russian regime);

- the media war, which exclusively or predominantly targeted allies of the Ukrainians.

These three levels, according to the operations manual of the Russian military commanders and Valery Gerasimov in particular, should be triggered simultaneously, interconnected in a single ‘hybrid war’.

In fact, however, since 2022 the three levels have ended up being arranged in a cause-and-effect sequence.

Having vanished the opportunities for a quick Ukrainian victory on the ground, which intimidated both Moscow and Washington, we moved in 2023 to a war of attrition where the economic factor became preponderant. Since then, the more Russian resources to continue the conflict have been depleted, the more importance the media war has gained to induce Ukraine’s allies to let go.

Having said that, let us look in detail at the events of the last three years.

In February 2022 , Putin tried to end the war against Ukraine, which he had unleashed exactly eight years earlier, with a full-scale invasion.

On the Southern front, due to the corruption or incompetence of Ukrainian officials, the bridges to the Crimea were not destroyed in time and the invaders occupied the regions of Zaporizhzhija and Kherson, only meeting serious resistance in the Mykolaiv region.

On the eastern front, the entire Luhansk region and the coastal city of Mariupol were occupied (where satellite photos of the cemeteries led to an estimated 75,000 to 100,000 dead).

On the northern front, however, against all expectations, the attack on the capital failed, due to poor logistics and some advanced weaponry the Ukrainians possessed (notably the Javelin anti-tank rockets and MANPAD anti-aircraft rockets). In withdrawing from the Kiev, Sumy and Chernihiv regions, the invaders massacred the inhabitants of entire towns including Bucha.

These atrocities against civilians in the occupied areas cut short the surrender talks that the Ukrainian government had attempted to initiate in Turkey.

In the meantime, a coalition of some fifty nations (mostly liberal democracies from the so-called ‘West’) launched some timid sanctions against Russia, such as exclusion from the SWIFT payments system, and procured belated military support, notably by sending twenty multiple HIMARS rocket launchers. The effect of these on the fragile logistics of the Russians was however devastating: combined with a brilliant intelligence strike, which knocked out the bridge between Russia and Crimea, it allowed the Ukrainian army to drive them out of Kherson and the Kharkiv region between September and November.

At this point, as more and more people on Joe Biden’s staff are testifying, the Russian dictator threatened the use of nuclear weapons if his regiments suffered a decisive defeat. Under US pressure, therefore, the Ukrainians did not annihilate the Russian army fleeing Kherson and merely asked the allies for armaments for a future ‘counter-offensive’.

The ‘Western’ democracies, in short, had chosen to entrust Ukraine’s salvation to the economic armistice.

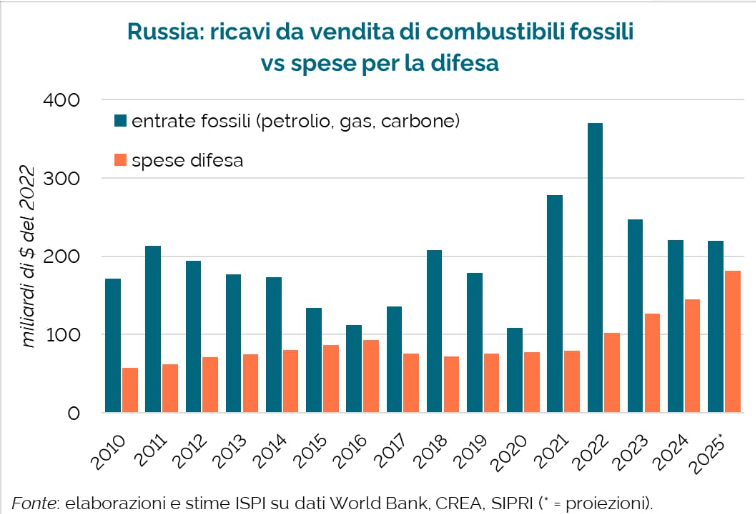

Thus, in 2023 , sanctions against Russian gas came into force and, starting in the summer, the ‘price cap’ on Russian oil. The aim was to force Putin’s regime to sell off its oil (moreover to Western-friendly countries such as India and Turkey) while earning too little to support the war effort. The move disrupted the regime’s coffers, but not entirely: several unforeseen events (including OPEC’s choices, strong Chinese demand and the Gaza conflict) kept the world oil price high, while Russia put a ‘ghost fleet’ of formally foreign cargo ships in the water to take advantage of it.

Meanwhile, the Ukrainian ‘counter-offensive’ failed, partly due to the destruction of the Kakhovka dam and the immense lake ecosystem it fed.

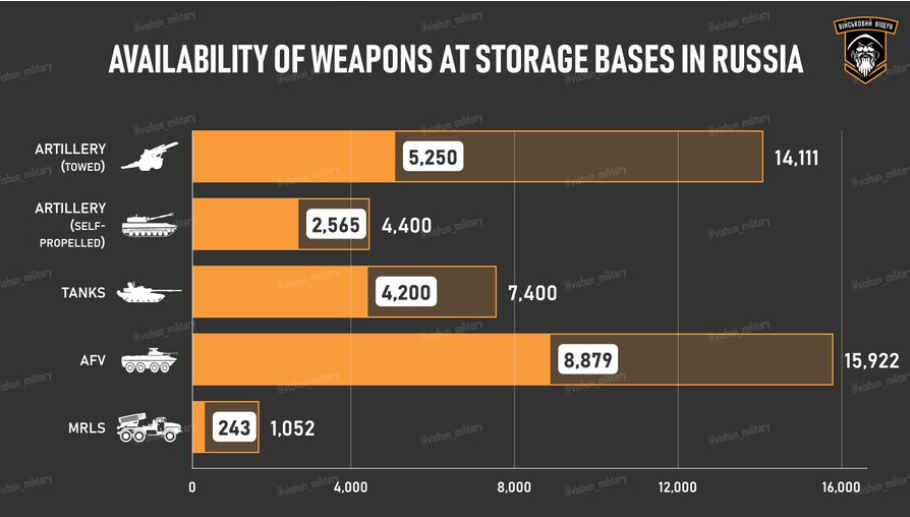

The only successes were achieved, once again, on a technological level. Thanks to reconnaissance drones, in fact, the Ukrainians were finally able to decimate the Russian artillery(now reduced to 8,000 pieces, of which 2,000 from the Stalin era, against 20,000 three years ago). Moreover, thanks to sea drones, they managed to dislodge the Russian fleet from the Black Sea for the first time since 1783. This allowed the world’s most fertile country to resume grain exports, which had previously only been possible to a small extent thanks to an artificial UN-mediated ‘Grain Initiative’.

And we come to 2024, the worst year for both contenders. On the ground, the Russian invaders have regained the upper hand. Thanks to FAB bombs, they have regained air supremacy. Thanks to Chinese manufacturers, as well as some complacent Western companies, they had hundreds of missiles a month to hurl at Ukrainian power plants, along with thousands of Shahed drones supplied by Iran. The abundant ammunition sent from North Korea and the possibility of using ‘human waves’ allowed them to advance eastwards, capturing almost 3,000 square kilometres of Ukrainian positions in Donetsk.

In addition, the dullness of commanders and the poor quality of equipment in entire units led to the desertion of over 100,000 Ukrainian soldiers. To compensate for the desertions and 400,000 casualties (including 120,000 dead), the Ukrainian parliament lowered the minimum age for military service to 25.

Despite these difficulties, Ukraine’s defenders responded with ingenuity.

Starting in March, they imposed ‘do-it-yourself’ sanctions on Russian oil, attacking refineries and their deposits with drones.

Then in August, they surprisingly occupied a small Russian province near Kursk, achieving psychological and other results.

The US and EU were confronted with the fait accompli that Russia can be attacked without major consequences, and gave the go-ahead for missile strikes against Russian airbases. Since then, also thanks to the entry into service of the first F-16 fighter jets, Russian air supremacy has vanished.

Moreover, the US and the EU can no longer ask for a populist freeze of the conflict along the current front line (as they did in 2014 and 2015) because Putin would never agree to cede a strip, albeit tiny, of homeland.

But the Kremlin overlord also had other bad news.

In a country where the working population is 75 million, the full weight of 800,000 dead and wounded (more than Britain had in World War II!), of a million men kept under arms, of at least a million emigrants and hundreds of thousands of Central Asian immigrants repelled after the Islamist massacre at the Crocus concert hall is being felt.

So, for some months now, new recruits (18,000 per month) have not been able to fill the void left by the fallen (22,000 per month), which, by the law of supply and demand, makes it necessary to increase wages and bonuses for those who enlist.

Official inflation has thus spiked to around 10%, although estimates of real inflation range between 15% and 50% (with peaks of 90% on some foodstuffs). A situation that would also be bearable, if in the meantime interest rates had not been raised to 21% to at least save the purchasing power of the rouble.

As a matter of fact, no Russian family or business is able to take out a loan today, except for companies involved in arms production. These are already indebted to the tune of more than 300 billion, which, having been invested in explosions around Ukraine that generate no return, will never be paid back to the banks.

The Russian Federation’s cash reserves are also running low: in the Sovereign Wealth Fund that had been accumulated with oil revenues there remain just over 350 billion Chinese yuan ($50 billion). In 2025, it is estimated that this will barely be enough to cover the staggering increase in military spending (from about 130 to about 180 billion) with the same amount of revenue from gas and oil. A parity that, moreover, has yet to be proven, after Ukraine closed the last gas pipeline between Russia and Central Europe and the US sanctioned over 180 ships of the ‘ghost fleet’.

Everything, in short, suggests that if Ukraine’s allies do not yield, and maintain the economic siege on Russia to the bitter end, Russia will soon have to withdraw its occupation force for lack of military and financial means.

This was the long and winding road that Joe Biden had chosen in November 2022, in order to prevent Putin from being reckless with atomic weapons at all costs.

And this is where the media war comes in. It is the only one the Kremlin can win now, but if it were won, it would give it narrow victory in the economic and field wars as well.

It is no mystery that in every European and North American nation there is at least one extreme right-wing party (and sometimes even one extreme left-wing party) that propagandises against Ukraine while excoriating and admiring Putinist Russia.

In some fortunate cases, such as Canada or Sweden, these parties are overshadowed by other forces that manage to preside over the classic right-wing agenda (anti-Islamism, anti-Wokism, climate scepticism, law and order) while disdainfully refusing to become tools of the Russian dictator. The same has happened on the left in Sanchez’s Spain. But in the vast majority of countries the Putin variant of populism has already devoured, or is on the verge of devouring, the original strain. It is so in France, Britain, Germany and Romania. It is so in Austria, Ireland, Belgium and Holland. As for Italy, support for the aggrieved Ukraine depends much more on the personal character of Giorgia Meloni than on the convictions of the average leader of Fratelli d’Italia.

In order to inflate the support of these Kremlin assets, many information masters have moved. TikTok, programmed by the Chinese regime, is the best known case. But also ‘X’, Elon Musk‘s new Twitter, grants preferential space to pro-Russian content. Telegram, founded in Russia, has only been able to operate in its country since it agreed to serve as a means of espionage. Let’s not forget, then, the ‘traditional’ media: recently, Italian newspapers astonished us all by flaunting on the front page a declaration of surrender by Volodymyr Zelensky that had never existed, except of course in the Kremlin’s press agencies.

Now, the question arises: with Trump’s triumph in the US, isn’t the media war already lost?

To what extent can the billionaire and his ‘MAGA’ movement be considered assets of the Kremlin?

Certainly, the cult of force at the expense of law unites Trump, Putin and some techno-oligarchs like Musk who have open sympathies for both. But it is also true that abandoning Ukraine would not be a show of force at all. Moreover, according to some think-tanks, it would cost the US the insane 800 billion over five years needed to defend further sovereign nations that Russia might then claim.

In conclusion, Biden has paved a path that in the medium term will lead to Ukraine’s rescue, while inflicting a very high human cost. Continuing to follow it is the most expedient of the choices currently available to Trump. Preventing the media war from reaping fatal successes in Europe, meanwhile, is the most convenient choice of those available to us.