Why blaming NATO for expansion is wrong, explained well

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 is often justified by the Kremlin with the argument that NATO ‘s eastward expansion represented (and represents) an existential threat to Russia’s security. This narrative, widely propagated by Vladimir Putin ‘s regime and revived by its flankers in the West, claims that the Atlantic Alliance would betray promises made in the early 1990s not to expand towards Russia’s borders. However, a historical and geopolitical analysis shows that this justification is unfounded, manipulative, and aimed at distracting attention from the true nature of Russian ambitions, which today we see unfolding not only in Ukraine, but also in Moldova and Georgia, and in perspective in the Baltic Republics, as well as in the attempts to condition democratic institutions in the former satellites of the Soviet Union, now full members of the European Union and NATO such as Romania, Hungary or Slovakia, or in the Western Balkans.

1. The promises of NATO expansion: myth or reality?

The Moscow regime claims that the West promised the Soviet Union not to expand NATO ‘one inch eastwards‘. This claim – which you will often find quoted – is based on verbal statements made by some Western leaders and political leaders during the German reunification negotiations in 1990. The then US Secretary of State James Baker, NATO Secretary General Manfred Wörner, or West German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher are often quoted in this connection.

Two fundamental studies help to clarify the issue of the alleged promises made to the Soviet Union: The Myth of a No-NATO-Enlargement Pledge to Russia (Mark Kramer, 2009, published by Harvard University’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies) and The United States and the NATO Non-extension Assurances of 1990: New Light on an Old Problem? (Marc Trachtenberg, 2020, published by the Wilson Center). Both papers predate the massive invasion of 2022 and, in particular, Kramer’s work even predates both the 2014 invasion of Donbass and Crimea and Putin’s return to the Kremlin after Medvedev’s ‘interlude’.

The two studies analyse the idea that the US or other Western countries promised not to expand NATO eastwards, and conclude that this promise was never formalised or included in binding agreements. Kramer and Trachtenberg converge on the idea that the focus of the discussions in 1990 was limited to the reunification of Germany and its status within NATO. Statements such as James Baker’s that NATO ‘would not extend one inch eastwards‘ referred exclusively to East Germany in the context of its integration into NATO. Both emphasise that the enlargement of the Alliance to other Eastern European countries was not on the agenda in 1990, as neither Western nor Soviet leaders foresaw the imminent collapse of the Warsaw Pact.

Kramer focuses on declassified documents and testimonies of key players at the time, showing that there is no evidence of an agreement to limit NATO expansion. Trachtenberg instead delves into the ambiguity of certain statements, highlighting how Soviet officials subsequently interpreted these statements more broadly, fuelling the narrative of a ‘Western betrayal’.

2. NATO expansion: an autonomous choice of the Central and Eastern European countries

The so-called ‘betrayed promise’ thesis of NATO’s non-expansion disregards the will of the countries concerned, those of Central and Eastern Europe, treating them as mere pawns in someone else’s game. In reality, joining NATO was an autonomous and conscious choice by these states, which, after decades of Soviet oppression, sought protection against a possible return of Russian imperialism.

Countries such as Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and the Baltic States had suffered invasion, occupation and repression during the Soviet period and in the imperial period before that. For them, NATO membership represented a fundamental guarantee of collective security, embodied in Article 5 of the NATO Treaty. On the other hand, for some, such as Poland, NATO membership represented a form of restraint and brake on potential autonomous initiatives to ensure their own security, including a nuclear arms race.

The accession process reflects these autonomous dynamics. In 1999, Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic were the first former Soviet countries to join NATO, followed in 2004 by seven more states, including Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Despite this, NATO maintained a cautious strategy, refraining from deploying permanent troops in the new members until 2014, demonstrating a cautious geopolitical balance with Russia.

3. The attempt to include Russia in global security schemes

The accession of Eastern European countries to NATO was not in opposition to Russia, but as part of an effort to collaborate and include Moscow in global security arrangements. Initiatives such as the Partnership for Peace (PfP) of 1994 and the so-called NATO-Russia Founding Act of 1997 aimed to build an inclusive security system, seeking to overcome tensions inherited from the Cold War.

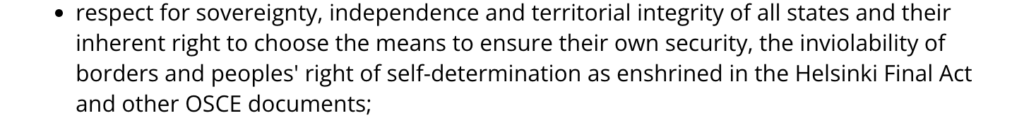

The Partnership for Peace spontaneously involved the former Warsaw Pact countries, which saw in it an opportunity to integrate themselves into the Western security system in an orderly manner. Russia also participated in the programme, underlining NATO’s willingness to include it in a constructive dialogue. This commitment was further formalised in the NATO-Russia Founding Act of 1997, which enshrined mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, transparency in military activities and non-hostility (pictured below, Principle No. 4 of Part I of the Founding Act).

The act also provided for the creation of a NATO-Russia Joint Permanent Council to facilitate regular consultations and dialogue on common security issues.

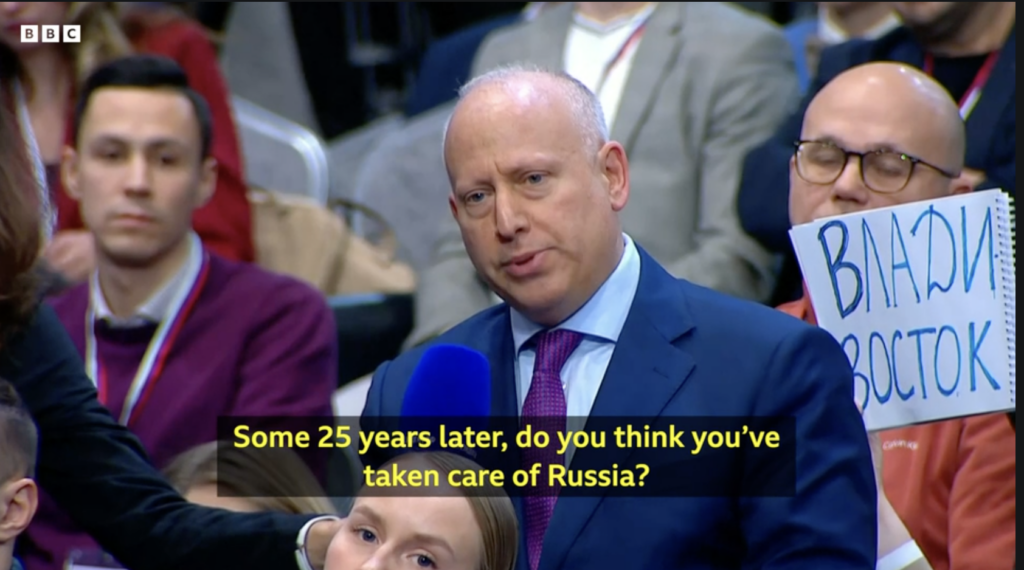

From Yeltsin to Putin, it was Russia that changed the line

What has changed from the signing of the NATO-Russia Founding Act in 1997 to the present day has been Russia, which in the meantime has moved from the Yeltsin presidency to that of Putin, in government for 25 years now. At his end-of-year press conference in December 2024, the Russian president acknowledged a significant change in Russian foreign policy. Responding to a question from the BBC’s Steve Rosenberg, who asked him whether – thinking back to when Yeltsin entrusted him with the leadership of the government 25 years ago and asked him to take care of Russia – he felt he had fulfilled his promises. Putin said, ‘I didn’t just protect her. I believe we have moved away from the edge of the abyss, because everything that was happening to Russia before and after was actually leading us towards a total loss of our sovereignty. And without sovereignty, Russia cannot exist as an independent state’. And again, ‘Western leaders patted Yeltsin on the back and even glossed over when he had had a little too much to drink‘. Statements that reflect Putin’s desire to mark a clear discontinuity from his previous political line, reaffirming Russia’s role as a sovereign and independent power on the global stage. Has the ‘tsar’ realised that in doing so he has admitted that the change of line and the violation of the pacts made were desired and implemented by Russia and not by the West?

Summary and Conclusions

The Russian narrative that NATO expansion represents a direct threat to Russia proves unfounded in light of historical facts and geopolitical dynamics. The allegations of a ‘betrayed promise’ are not borne out by the documents or testimonies of the protagonists, but are rather a later construction used to justify policies of aggression and imperial reassertion. On the contrary, NATO enlargement was the result of autonomous decisions by the countries of Central and Eastern Europe that chose the Alliance as a security guarantee against possible returns of Russian expansionism. Moreover, NATO actively sought to include Russia in global security schemes, as evidenced by initiatives such as the Partnership for Peace and the NATO-Russia Founding Act, which could have provided a platform for lasting cooperation. However, the aggressive line taken by the Kremlin with Vladimir Putin has undermined these efforts, bringing the confrontation between Moscow and the West back to levels of tension above those of the Cold War.

Want to delve further? We recommend this very comprehensive work by Chatham House